A backstory on moments in the lives of John Lewis and C.T. Vivian

This is worth reading and sharing especially if you don't know much on these two

Welcome to my freemium newsletter by me, King Williams. A documentary filmmaker, journalist, podcast host, and author based in Atlanta, Georgia.

This is a newsletter covering the hidden connections of Atlanta to everything else.

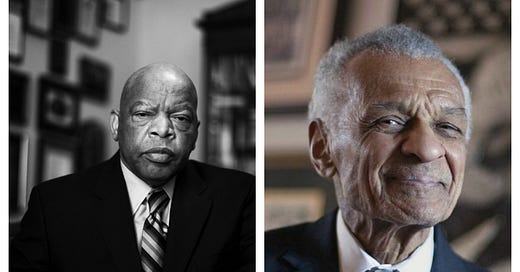

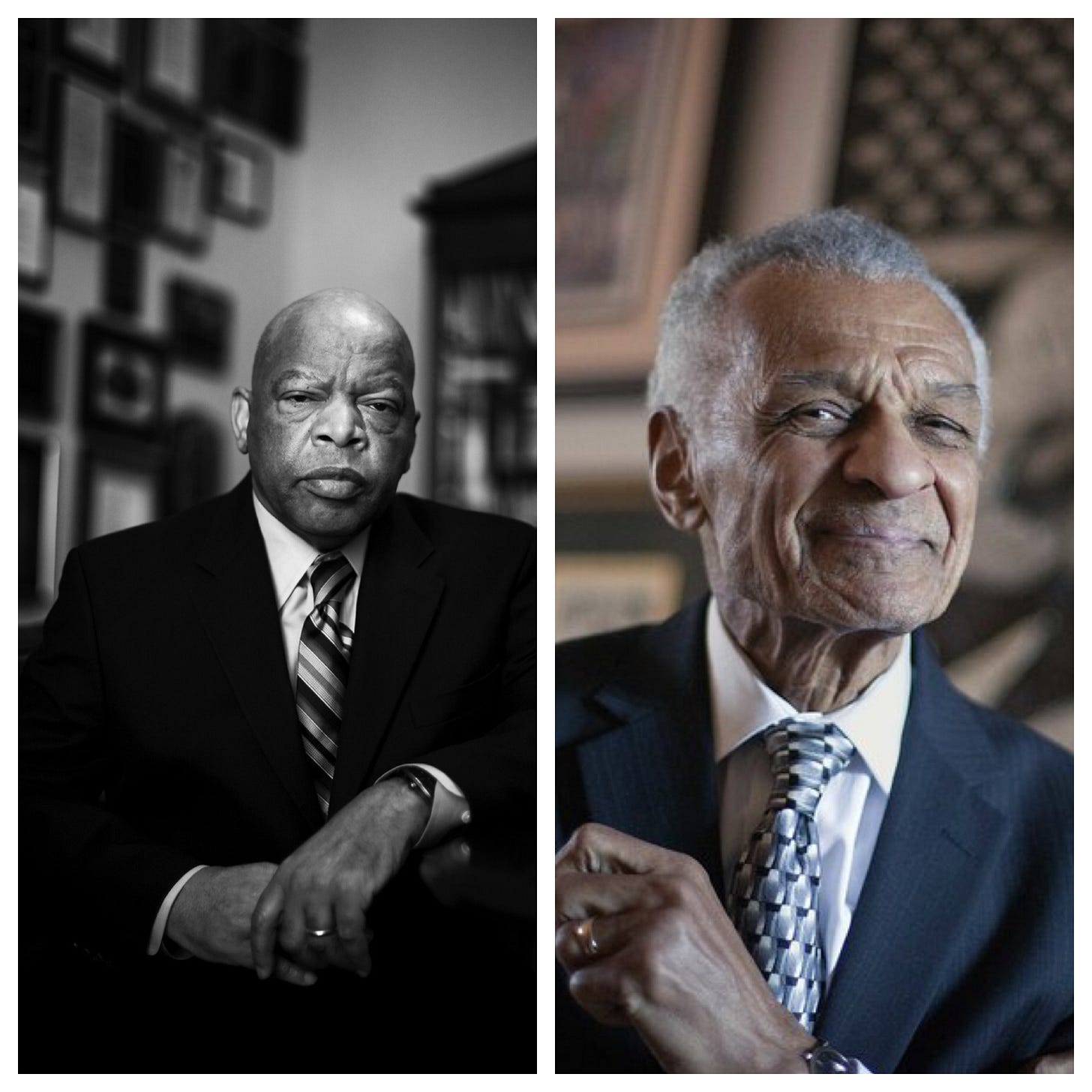

Civil Rights icons, Congressman John Lewis (L) and Reverend C.T. Vivian (R)

Edited by Alicia Bruce

The purpose of this article is to help provide a small, amount of backstory on John Lewis, C.T. Vivian, and the Civil Rights Movement, as well as to understand the world that they had to endure.

This is the backstory of two men who both entered the national spotlight at the same time and were called back home on the same day.

John Robert Lewis

Lewis was born in 1940 as the third of ten children to sharecroppers Willie Mae and Edward Lewis in Troy, Alabama. Lewis initially thought he would become a preacher and had very limited contact with White Alabamians until he was a young child.

Lewis wasn’t aware of what an integrated society looked like until he went to visit a relative living in Buffalo, New York at age 11. Lewis also would first hear Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (MLK) on the radio at age 15, as a result of the ongoing Montgomery Bus Boycott. He would meet Rosa Parks two years later at age 17 and MLK a year later at age18.

Lewis attended college in Nashville, at the American Baptist Theological Seminary, where he would graduate, becoming an ordained Baptist minister. Afterward, he stayed in Nashville to attend Fisk University, a historically Black college (HBCU).

It was at Fisk that Lewis would be introduced to non-violence, political organizing and also meet a future lifelong friend at the school, a captivating speaker from Illinois named C.T. Vivian.

Cordy Tindell Vivian

Photo via Horace Cort/Associated Press

C.T. Vivian was born in 1925 in Booneville, Missouri, but would spend his formative years growing up in Macomb, Illinois.

Vivian would become active politically early in his life, as a student at Western Illinois University, remaining politically charged in the Illinois area until moving to Nashville to attend the American Baptist Theological Seminary in 1959.

Vivian helped found the Nashville Christian Leadership Conference (1958-1964), an organization created after a January 1958 Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) conference in Atlanta. Vivian also helped to organize the first Nashville sit-ins in 1960 in addition to the first civil rights march in the city in 1961. In that same year, Vivian participated in the inaugural Freedom Rides in May of that same year alongside a 21-year-old John Lewis.

Vivian worked in company with Martin Luther King Jr. as the national director of affiliates for the SCLC and was also called “the greatest preacher alive” by King.

Fisk University and the role of HBCU’s during the civil rights movement

Nashville Mayor Ben West (R), C.T. Vivian (C), and Diane Nash (R), photo via Nashville public library

The legacies of both CT Vivian and John Lewis intersect because of the role of Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. Fisk in particular was known as the preeminent Black college at the time as well as one well known for student activism.

In 1930, Fisk became the first HBCU to gain accreditation by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS), drawing some of the brightest Black students from across the country.

After enrolling at Fisk, a young John Lewis would cross paths with an unerring transfer student from Howard University in Washington, D.C., named Diane Nash. Nash was already challenging segregation on her own in Nashville and quickly rose to be a powerful activist in Nashville.

Nash, Lewis, and the older C.T. Vivian proved to be quite a powerful combination, so much so that she was invited by famed organizer Ella Baker (aka the G.O.A.T.), to be a part of the inaugural Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in 1960 with several other students from the Nashville area.

Nash and Vivian led the Nashville sit-in movement which was notable in that within three months, lunch counters in the city were desegregated, a stark contrast to the more infamous Greensboro sit-ins which started less than two weeks prior.

The Two James: Farmer and Lawson

While many will point to the relationship between Vivian and Lewis with MLK, it’s important to know two others who also had a profound impact, James Farmer and James Lawson.

James Farmer

The Co-founder of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and architect of the Freedom Rides of 1961.

He was also one of ‘the Big Six’ civil rights leaders which included John Lewis, MLK, Roy Wilkins, Whitney Young, and in his opinion, Dorothy Height of the National Council of Negro Women. This is a noticeable choice by Farmer to include Height and not A. Phillip Randolph.

The press at the time would exclude both Height and Lewis from the narrative, calling the leaders ‘the Big Four’ instead. And many today still list Randolph instead of Height in the Big Six. Farmer in his own memoir noted this exclusion of Height was because of sexism and he wanted to make made sure Height was included in the narrative.

James Lawson

Lawson introduced the principles of Gandhi to MLK and was asked by him personally to come back to the US after sending years as a Methodist missionary in India before returning to the states as a divinity student at Oberlin College.

In 1959, Vivian met Lawson who was teaching non-violent strategies to a young Diane Nash and the Nashville Student Movement, which included several notable students, civil rights leaders Bernard Lafayette, James Bevel, and of course, John Lewis. Lawson would enroll at Vanderbilt University in Nashville as a student at the School of Divinity.

On April 19, 1960, with the training of Lawson, Vivian and Nash led 4,000 peaceful demonstrators to Nashville's City Hall, to discuss racial discrimination with then-Mayor Ben West.

Lawson also organized the Nashville Student Movement's successful sit-in campaign which lasted from February to May of 1960 and was expelled as a result.

The Freedom Riders

Both C.T. Vivian and John Lewis entered the national spotlight in 1961 as one of the original 13 freedom riders. The freedom riders were a collective of black-and-white nonviolent activists who sought to desegregate buses.

These buses were on a series of stops in the south between Washington, D.C., and New Orleans. The bus stops may national television as several stops featured filmed acts of domestic terrorism including beatings and on one-stop, in particular, the entire bus being firebombed with Klansmen locking the door on the passengers.

photo via the AJC, author anonymous

The Freedom Rides of 1961 were actually based on a similar idea 14 years prior, led by Baynard Rustin (one of the earliest known Black gay activists) and James Forman.

The 1961 Freedom Rides, were organized by CORE and modeled after the organization’s 1947 Journey of Reconciliation. This attempt was similar to the 1961 Freedom Rides, both were an integrated group of bus riders who attempted to test the limits of segregation in the south. Both also featured anti-war and civil rights activist James Peck.

However, the 1947 version was explicitly done to test the waters on the recent 1946 Supreme Court decision of Morgan v. Virginia, which found that segregated seating was unconstitutional.

While the 1961 Freedom Rides tested a 1960 decision, Boynton v. Virginia, which stated that segregation of interstate transportation facilities, bus terminals, and lunch counters was also unconstitutional. Unlike the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation, the 1961 Freedom Rides included women.

John Lewis almost missed the Freedom Rides

According to Lewis’s own biography he nearly missed his opportunity to get on the bus. This is confirmed by fellow Nashville student non-violent activist, Freedom Rider, and friend, Bernard Lafayette in a recent New York Times op-ed.

According to Lafayette, the idea to desegregate a Greyhound bus was already in the works between himself and Lewis in the holiday season of 1960, several months before the Freedom Rides in May of 1961. The two actually did integrate the buses on a ride home for the holiday:

During the 1960 Christmas vacation holiday, John and I decided on our own to desegregate a Greyhound bus in Nashville. That was before the Freedom Rides. The Greyhound bus station had just one ticket counter.

They used to have separate ticket counters, separate lunch counters, separate waiting rooms, separate restrooms. But now this bus station was completely desegregated. So we got our tickets at what used to be the white-only ticket counter.

And we just got on the bus. I sat behind the driver in the first seat. John sat across from me in the front row. The bus driver insisted that we move to the back, but we didn’t.The driver pulled back into the bus station and tried to get support.

But he returned with no results. So, he had to drive us.

A police killing is why the March on Selma happened in the first place

One of the things not often mentioned is why the March on the Selma happened in the first place.

In February of 1965, Jimmie Lee Jackson, a civil rights activist in Marion, Alabama was shot and killed after police attacked at a night protest. That protest was led by C.T. Vivian in Marion, Alabama and it was this killing that galvanized the Black community of Selma as well as activists already on the ground.

It was this killing of Jimmie Lee Jackson that lead to the March on Selma by John Lewis and so many others in what was known as ‘Bloody Sunday’ the following month.

We need to step back a minute.

Alabama was a hotbed of violence during the civil rights movement and Selma in particular was the most inhospitable place to be as an activist. It was Selma’s hostile response to Black people registering to vote that brought out activists like MLK, John Lewis, and organizations like SNCC to the city.

As the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed into in July of 1964, there was a renewed focus on passing a national voting rights act. By January 1965, several national voting rights organizations came to Alabama and began moving into other communities within the state to help people register to vote. These national groups came alongside several local initiatives and organizations already working in the state to put more pressure on pursuing the right to vote.

This set off a wave of mass arrests, these arrests were in such large numbers it led to people being sent to work camps, due to the overcrowding of jails. Many of these civil rights workers and protestors were placed in locations like Camp Selma, which was the biggest. This resistance to voting in Alabama is what led people like Jimmie Lee Jackson, to become active in the movement as he had tried previously four times to register to vote.

The protests in Selma eventually went to being held both day and night, which was a rarity at the time. Night marches were very rare because of the potential of an increased probability of violence from unhinged racists.

It was Vivian who called for a night march to be held in Marion, Alabama on February 18th, 1965. Selma’s sheriff, James ‘Jim’ Clark got a hold of this information and called in several different units of police from around the state including Alabama state troopers and other Alabama law enforcement agencies.

The police preceded to immediately attack the estimated 500 protesters at the march, causing them to disperse in every direction.

Jackson took off running once the police attacked the protestors and ran into a local establishment, Mack’s Café, where he was met by an officer who shot him twice in the stomach. Jackson eventually succumbed to his wounds a few days later, but not before being served a warrant for his arrest by the then-head of the Alabama State Troopers, Col. Al Lingo.

To make things worse, the Alabama state Senate denounced the charges of dereliction against the officers who attacked the protestors in Marion.

After his funeral, Jackson’s gravestone was riddled with bullets up by unknown assailants, this practice was exclusively done out of disrespect and for intimidation purposes.

Selma was awful, more than how it’s presented today

It got so bad in Selma in the early 1960s that the Department of Justice actually sues the Selma police department for unconstitutional efforts regarding voter suppression in 1964, the first of its kind.

Take some time to check out this video from Atlanta Journal-Constitution on C.T. Vivian

In that lawsuit, Selma Sheriff Jim Clark (who you see in the video above punching CT Vivian) and local prosecutor Blanchard McCloud, were both previously sued by the federal government for their handling of Blacks in Selma. And it was McCloud who was supposed to investigate the shooting of Jimmie Lee Jackson.

According to McCloud’s investigation, McCloud stated that he had a signed confession of the shooter (an Alabama state trooper) but refrained from identifying the shooter, saying that the shooter claimed self-defense. This was on top of no public information given, no mention what information was submitted to a grand jury, with the only information being that the state trooper was not charged.

It wasn’t until forty years later that the shooter publically confessed to the killing to a reporter from the local paper, The Annison Star in 2005 that he did in fact murder, Jimmie Lee Jackson. This is on top of Fowler also killing an unarmed Black motorist the following year in 1966.

The killer, former Alabama state trooper, James Bonner Fowler, claimed that Jackson was trying to kill him during the altercation by reaching for his gun. Fowler was sentenced to six months in jail in 2010 and serving only 5 months. Fowler would die five years later, with a big part of his lenient sentence was his age at sentencing (then-77-years-old) and a question of whether a life sentence would solve anything.

The Three Selma Marches

One of the biggest misconceptions about the civil rights movement is regarding the March on Selma.

Through a combination of folklore and selective omissions of Black history taught in school, this march has been presented in the public as a singular event, bloody but triumphant event, often presented without context.

The March on Selma is presented as a victory lap for Martin Luther King and the Civil Rights movement, and more importantly, was the sole reason that the Voting Rights Act of 1965 became signed into law. This isn’t completely correct.

There wasn’t one march in Selma, Alabama but three of them.

The first Selma march also known as ‘Bloody Sunday’ is the most well known. That protest being led by John Lewis and Atlanta’s own Hosea Williams was supposed to be a nearly 50-mile march from Selma, Alabama to the state capital of Montgomery, Alabama to register thousands of Black Alabamians to vote.

It was a little over three weeks after Jackson’s killing, that an estimated 600 protestors showed up on the Edmund Pettis Bridge on Sunday, March 7th. This protest was being reported on by several national reporters and saw a showdown between the peaceful protestors and several hundred armed Alabama law enforcement members.

This showdown resulted in the peaceful protestors being tear-gassed and beaten on live television by Alabama law enforcement changing the national perception of the movement.

An interruption of a movie on the holocaust television is what helped the bring Selma’s ‘Bloody Sunday’ to the masses

The March on Selma was the first time many Americans actually saw the horrors of the Jim Crow south uncut and unedited.

It was also the first time many saw what protestors actually were encountering by law enforcement. But it was a specific 1961 film being aired on television at the time that actually primed the audience to the injustices of what happened in Selma.

The incident was so powerful because in the 1960s there were only three television stations in most of the US and was much easier for Americans to get the news all at once. And on this particular night, the image of the protests was interrupting a Sunday night rebroadcast of the 1961 film, “Judgment at Nuremberg”, a film on the horrors of the holocaust.

In what was a bloodily serendipitous moment for the movement, many the images of protestors being beaten and tear-gassed did more to change the perception of the movement for Americans. Millions of people were already processing one oppressive horror of the film and this immediate juxtaposition of police brutality prompted many White Americans to really see for the first time the horrors being faced by protestors.

The Second and Third Marches

John Lewis, despite being injured at the first march returned and is chronicled by The New Yorker magazine in 1965, in a long essay entitled ‘Letter from Selma’. What’s interesting is the labeling of Lewis’s speech at the time as ‘radical’:

One marcher applauded, and was immediately hushed. Then there was the succession of speeches, most of them eloquent, some of them pacific (“Friends of freedom,” said Whitney Young, of the Urban League), others militant (“Fellow Freedom Fighters,” said John Lewis, of S.N.C.C.), and nearly all of them filled with taunts of Governor Wallace as the list of grievances, intimidations, and brutalities committed by the state piled up.

The Second March

The second march on Selma took place a few days later on March 9th, with this time being led by Martin Luther King, who successfully led a new crowd of an estimated 2,000 protestors over the Edmund Pettis Bridge only to be stopped by another wall of Alabama law enforcement. It wasn’t until King led a prayer that the protestors were allowed to continue by Alabama law enforcement on the way to Montgomery.

But later that evening James Reeb, a White minister from Boston who came down to Selma to join the march was killed that evening and it was his murder that brought even more national attention on Selma. This attention prompted then-President Lyndon B. Johnson to call Governor George Wallace himself to order him to have the Alabama national guard to protect the protestors on the next march led by King towards Montgomery.

The Third March

The third march on Selma took place on March 21st but due to Bloody Sunday and the killing of James Reeb, begat a showing of over 25,000 protestors arriving at Montgomery.

This march was symbolic and the thought of more violence ensuing was one of the reasons leading congress to create a voting rights law. But it wouldn’t be until August of that year that the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed. A bill that was finally signed on August 6, 1965, after 5 additional revisions to expand protections.

The March on Washington

The March on Washington was the height of the Civil Rights movement. The period of 1960 to 1963 saw a rapid period of national notoriety for the movement, culminating at the National Mall in Washington D.C. on August 28th, 1963.

One of the biggest issues still not addressed was the passage of a national civil rights bill, a bill that was still being considered by then-president John F. Kennedy (JFK). The March on Washington was a pivotal moment and was looked at as a way to finally have JFK to sign a bill into law.

There John Lewis was one of only six speakers, as well as being the youngest. Lewis was essentially the voice of the youth at 23-years-old, and here is where a part of the legend of John Lewis was not taught in school.

His original speech at March on Washington was deemed too radical, by James Forman, a veteran civil rights activist who worked for SNCC from 1961-1966 before joining the Black Panthers, and it was Forman who re-wrote Lewis’s speech.

You can read a little about that story in the 2005 New York Times obituary of James Forman:

The White House believed the fiery language in Mr. Lewis's speech could harm passage of its civil rights bill. Mr. Forman persuaded Mr. Lewis to remove a threat to someday march on Washington "the way Sherman did" through Georgia, a phrase thought to be less than felicitous to Southerner ears.

But with the full endorsement of A. Philip Randolph, the chief organizer of the march, they kept another provocative phrase: "We're involved in a serious revolution. The black masses are restless.”

from the 2005 obituary of James Forman

The March on Washington led to the then-Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), J. Edgar Hoover to start targeting King as well as several other Black organizations in what was known as the COINTELPRO program. Many of those same tactics of surveillance, informants, misinformation campaigns, and starting group in-fighting are still used today.

Many of these have been unearthed being used against the Black Lives Matter movement and selected activists as early as 2014.

From Civil Rights to Black Power

The period of 1960 to 1963 was the height of the civil rights movement, and by 1965 several other elements of Black political activism were changing the direction of social movements.

This includes the rise of Malcolm X, prominence of the Nation of Islam, an increased focus on Black self-defense, and frustrations with the civil rights movement.

These frustrations were primarily regarding the rate of social change, slow-moving policy changes, a decade of people dying at the hands of racists, an economic system that still had not produced for Black Americans, rampant police brutality, and the resulting uprisings (NOT riots) which took place as a result.

Within one year after Selma that John Lewis is kicked out of SNCC in 1966 (as mentioned in his memoir) and was replaced by the fiery activist, Stokley Carmichael who would take over.

Carmichael would later be one of the first person to utter the phrase ‘Black Power’ in national media, solidifying a cultural shift that was already years in the making.

That split of the Black activist community went in two paths:

one, pursue a continually perceived passive, non-violent goal of civil rights, focusing on interracial cooperation with the goal of societal integration and racial reconciliation.

the other, pursuing an inward, isolationist stance of Black Power focusing on self-reliance, self-defense, and not depending on outside forces for the Black community.

For those non-violent civil leaders like John Lewis and C.T. Vivian, the activism continued in the 1960s but at a much less successful measure. And by the 1970s both men did what many Black people from across the country did, they moved to Atlanta.

The next act of John Lewis and C.T. Vivian

For Lewis,

After his time in SNCC, Lewis moved to New York City to work as the field director for the Field Foundation, lasting less than a year before moving back to Atlanta. In Atlanta, Lewis would work for the Southern Regional Council, the Voters Education Project, in addition to completing his degree from Fisk University.

Lewis attempted to make the pivot from activist to politician by first unsuccessfully attempting to run for the US 5th District office in 1977. After his defeat, Lewis became the US ambassador to then-president Jimmy Carter and after carter losing his re-election campaign in 1980, he returned to be a city council member until 1986.

Lewis ran again for office in 1986, winning the seat, a seat he held onto until he passed two weeks ago.

In that 1986 race, he defeated fellow civil rights leader Julian Bond and eventually attaining a comeback win a runoff against Bond after he failed to garner the majority vote in the first election.

Lewis would also pen several books on his life including his 1998 autobiography, another in 2012, and his final book in 2017. In 2013 became the first Congressperson to have a graphic novel written about him entitled March created by Andrew Aydin and Nate Powell.

It was this graphic novel that led to him showing up as a cosplay version of himself at Comicon in 2015.

For Vivian,

Vivian published a book in 1970 entitled Black Power and the American Myth, which was the first book written from someone directly involved in the movement. Vivian continued his activism in the 1970s by starting organizations such as the National Anti-Klan Network (which later renamed as the Center for Democratic Renewal) and a consultancy firm called Black Action Strategies and Information Center (BASICS).

In the 1980s Vivian was apart of the campaign to elect Jesse Jackson for President and in the 1990s he helped to establish Capital City Bank, a Black-owned bank in Atlanta, which closed in 2016. And in 2008, he founded the C.T. Vivian Leadership Institute as well as a career as a distinguished speaker on the Civil Rights Movement.

Both men in 2013 would receive the congressional medal of Freedom from the country’s first Black president, Barack Obama.

What’s next?

I would first contact Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (KY), who since a 2013 Supreme Court decision has held back passing legislation regarding restoring the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

This is on top of McConnell’s even more dangerous but successful efforts to push hundreds of regressive and in some cases, unqualified federal judgeships. McConnell has also pushed for the regressive Supreme Court appointments of justices is Brett Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch, who both have already struck down cases regarding voter suppression.

The best you could do is donate to McConnell’s challenger in November, Amy McGrath, and get involved in her campaign.

There is also a petition to rename the Edmund Pettis Bridge, which is named after actual KKK Grand Dragon and Senator in Selma. A bridge which coincidentally enough opened the same year as Lewis was born.

In Atlanta, I would say if we’re going to rename things in Atlanta, why not rename Grady High School after C.T. Vivian instead of the racist Henry Grady? There was already a student led-movement to try to do that, and I hope it comes back.

John Lewis’s old seat

The Democrats have now selected current the Democratic Party of Georgia’s state leader and State Senator Nikema Williams, to represent Lewis in Congress.

Williams will now also be in the November 2020 election against Republican appointee Angela Stanton-King, yes as in that King family. She is the goddaughter of Alveda King, Martin Luther King Jr’s niece.

What’s at stake

MLK, John Lewis, and everyone who’s volunteered in some capacity during the Civil Rights movement may be saddened by today’s state of affairs.

What can we do?

Vote.

Help register others to vote. And check your voter registration status: https://georgia.gov/register-vote

Request an absentee ballot: https://sos.ga.gov/index.php/Elections/absentee_voting_in_georgia

Volunteer to be a poll worker: DeKalb County, Cobb County, Fulton County, Gwinnett County, and visit the state of Georgia’s website for more informations.

You can sign up to help me send pizza to people at the polls in metro Atlanta in November.

And if you haven’t already, I suggest checking out the documentary on Lewis, Good Trouble which came out on-demand two weeks ago.

It’s on us now

It’s not just brother Lewis and brother Vivian, we’ve lost quite a few legends of the civil rights movement within the last year especially. Joseph B. Lowery, John Lewis, C.T. Vivian, Juanita Abernathy, and Elijah Cummings have all died within the last year.

John Lewis entered and exited on the national scene at signs of protest.

In John Lewis’s life, he was one of the few people to actually have a career that spans from the Civil Rights Movement to the Black Power era to Black Lives Matter movements first hand.

From emerging on the front lines as a teenager in Selma Alabama to exiting at Black Lives Matter plaza in Washington DC. John Lewis started where he finished where he started.

John Lewis’s last public appearance at Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington, D.C.

Unfortunately this time they won’t get to see the victory that is before us.

So long and good night brother John and brother Cordy.

-KJW

If you haven’t subscribe now please subscribe to my newsletter do you have the option of free, $10 a month, or free or $100 for the year.