MEGA MARTA

This isn't the first time an expansion this large was proposed but it's the first time this many people are talking about it

Welcome to my newsletter by me, King Williams. A documentary filmmaker, journalist, podcast host, and author based in Atlanta, Georgia. This is a newsletter covering the hidden connections of Atlanta and everything else.

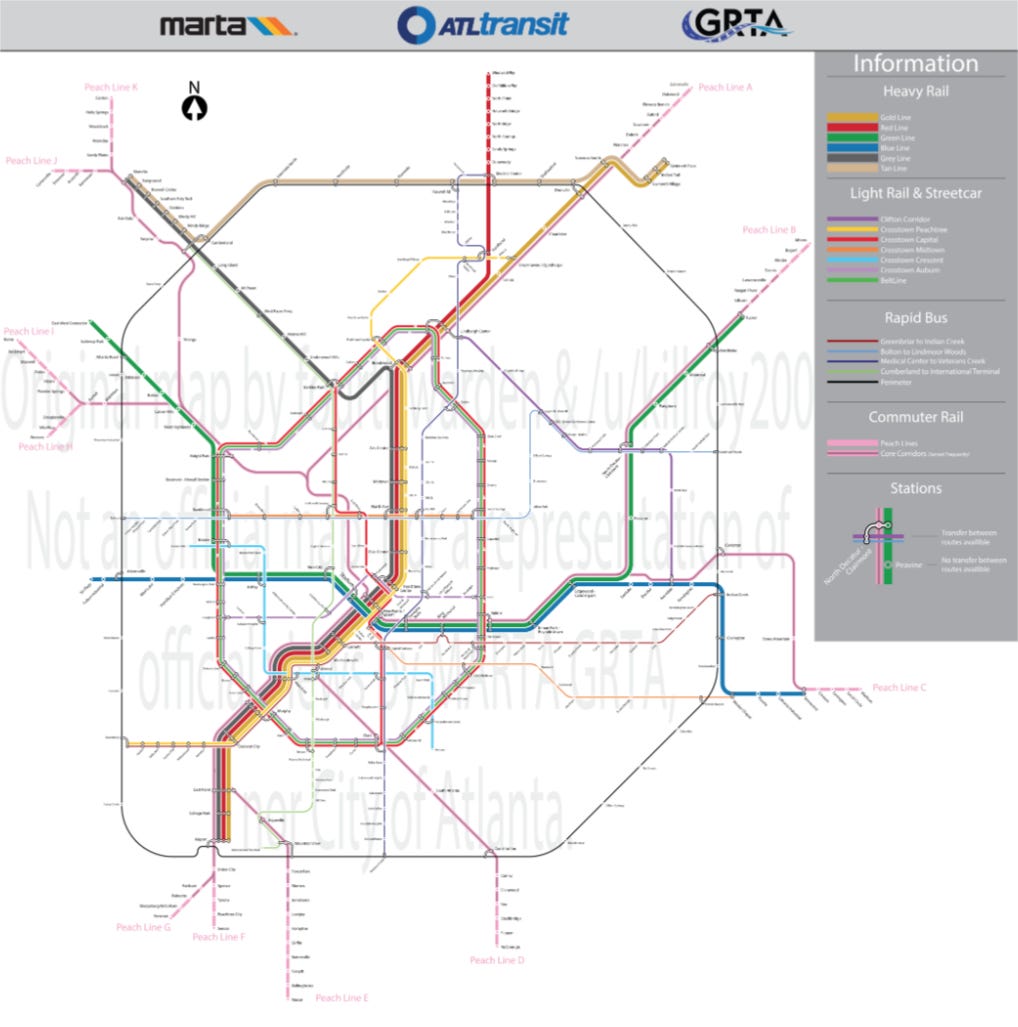

A new user-generated MARTA Map goes viral

A three-month-old post from the r/transit subreddit has gone viral in various Atlanta social media circles over the last two weeks. The original post, from Reddit user thesouthdotcom features an expanded MARTA heavy rail plan that would see the current 48-mile system expanded to a 275-mile system.

This proposed expansion would see an additional expansion from the only two heavy rail counties where MARTA resides, DeKalb and Fulton, into three additional counties, Gwinnett, Cobb, and Clayton.

The map would expand from the current cardinal direction configuration of MARTA into a system similar to that of WMATA, Washington DC’s regional transit service. In this map, Atlanta would see a variety of N/S/E/W train stations and routes, all distributed into smaller, color-coded transit nodes with an inner loop of transit (in grey).

This map seeks to connect metro Atlanta towns and cities via a train station. This map has more stops in the more northern and suburban counties in Cobb and Gwinnett, then expands Fulton’s MARTA map by adding a few additional stops. While also keeping all of the current MARTA train stations.

The current MARTA Map

The current MARTA map is a N/S/E/W map that features 54 miles of trains.

The map reflects the lack of buy-in from the original transit proposition in all five core counties. The lack of buy-in resulted from a coordinated effort to stop transit in the initial designs of MARTA. Overlapping during the era of white flight from the city of Atlanta and the growth of the suburbs, racist dog whistles, door-to-door campaigns, and a media campaign that successfully dissuaded the expansion of transit from the city into the suburbs.

Now, over 50 years later, many of those same ideas persist. As a result, MARTA’s expansion has never grown despite its continual need.

2. Mass transit in Atlanta before MARTA

Atlanta has been a mass transit hub for most of its existence. Passenger and commuter rail was integral to Atlanta's economic and residential development from the 1820s until the 1940s. Streetcars, trolleycars, heavy rail, and eventual buses, all before the 1950s, abound the city streets. But a combination of factors, including rising operational costs, corporate consolidations, white flight, the development of the suburbs,

Streetcars, the longest and most common form of mass transit in Atlanta

Atlanta has been a mass transit hub for most of its existence. From the 1860s to the 1940s, streetcars were the city's primary means of mass transit.

Starting with the city’s first modern streetcar, the Atlanta Street Railway, in 1866. This was succeeded by several other privately created street car companies throughout the late 1800s. Atlanta’s streetcars grew steadily from the late 1800s until the 1920s, often in affluent areas and connecting the east and west sides of the city.

All streetcar companies were private entities at this time, and service was mostly confined to a corridor of Decatur, eastern DeKalb, and the city of Atlanta. Where many of the current-day MARTA bus and train routes still operate. Including a wave of consolidation happening between the 1890s through the 1920s. Leading to the eventual unification and ultimately dissolution of streetcars and the last mass-scale transit system in Atlanta.

The consolidation years 1890-1930

In 1891, the Atlanta Consolidated Railway Company was formed. The company was notable for its attempt to purchase and consolidate several competing rail companies and the public rift between Atlanta & Edgewood Street Railroad Company founder Joel Hurt and Henry Atkinson.

Joel Hurt

Hurt, a local developer and rail tycoon, helped to create Atlanta’s first electric streetcar line in the 1880s. Hurt’s company would continue its expansion within Atlanta through new tracks and the acquisition of other companies, eventually leading to 200 miles of railways.

This led to the development of Atlanta’s first skyscraper, the Equitable Building, which also became the downtown end loop of his streetcar line. Hurt was also one of the co-founders of Trust Company of Georgia, a bank known as SunTrust Bank decades later through a series of mergers, which would eventually become Trust Bank.

Henry Atkinson

Hurt’s rival, Henry Atkinson, would later become a shareholder and eventual owner of Atlanta's Georgia Electric Light Company of Atlanta; that company would eventually evolve into the current-day energy company, Georgia Power. The success of its efforts to electrify Atlanta’s streetcars would pave the way for the company’s future as the southeast’s leading energy supplier.

The creation of Georgia Power and the unified streetcar system

Atlanta’s streetcars grew steadily from the late 1800s until the 1920s. All streetcar companies were private entities at this time, and service was mostly confined to a corridor of Decatur, eastern DeKalb, and the city of Atlanta. Where many of the current-day MARTA bus and train routes still operate.

During the 1920s-1940s, a wave of consolidation entered as streetcar ridership peaked. Despite the success in overall ridership, the costs associated with maintaining several different types of transit systems and consolidation costs took their toll. The costs needed to maintain and upgrade the electric trolley system began to mount as personal automobiles took off.

The 1950s and 1960s saw the dissolution of the streetcar as the primary means of transit. This saw the rise of secondary mass transit options, taking up more ridership through trackless trolleys and buses, in addition to the expansion of personal automobiles.

The end of the streetcar system

Meanwhile, the city’s white populations moved further away from the downtown and midtown sections of town, further north, west, and south. The biggest factors were the rise of Black residents moving into predominantly white communities, the slow-moving desegregation of public facilities, the integration of public schools, the GI Bill, the new construction of whites-only communities, and the eventual creation of highways I-75/85/20.

Since the 1920s, many streetcars in Atlanta were operated by the Georgia Railway and Power Company (now known as Georgia Power), founded in 1902 to develop electric streetcars in Atlanta. For the next 20 years, streetcars in Atlanta would reach their peak. As the city of Atlanta grew, so did ridership. Despite the growth, the costs of maintaining the fleet and increased competition would lead to an eventual de-emphasis on streetcars.

By the 1930s, streetcars began to be replaced by trackless trolleys and buses. Throughout their run, streetcars were among the few places in Atlanta where segregation was not as easy to enforce. As racial tensions enflamed Atlanta again after WWII, the need for greater separation between the races became more prominent. Those who could avoid Blacks and race mixing via cars did.

By the 1940s, with the war ending, the returning home of soldiers to a still-growing Atlanta, and a reshuffling of the racial demographics of neighborhoods, streetcars would see their eventual end. The last streetcar in Atlanta was in 1949, allowing its supporting infrastructure to be removed and newer paved roadways to accommodate personal automobiles. This removal and the shifting racial demographics of neighborhoods in early-stage white flight era Atlanta would further de-emphasize public transit. By the 1950s, cars allowed for further expansion from the downtown core, further north and westward, in parts of the city not served by the old streetcar lines.

3. The Atlanta Transit Company, MARTA before MARTA

As several factors led to the end of the streetcar, many of these factors became more prevalent in developing what would eventually become MARTA. MARTA would be the successor to the post-streetcar era of Atlanta. An era best defined by the management of the Atlanta Transit Company. Operating from only 1950 to 1972, the Atlanta Transit Company would be a precursor to MARTA and the impetus for still needing regional transit.

The Atlanta Transit Company, the original MARTA

Atlanta Transit Company, the forbearer to MARTA, ceased operations in 1972. The Atlanta Transit Company was formed after the closure of the streetcar in 1949. The Atlanta Transit Company was the city’s local monopoly on mass transit. Operating all of the city’s streetcar trolleys, trolleybuses, buses, routes, infrastructure, and employees of decades of consolidation.

This formation allowed Georgia Power to divest of its mass transit investment fully. The company's start was notable for a 37-day work strike, which operated as a bellwether of its future. The company phased out all its trolley buses by 1963, removing all the former electric wiring throughout the city. By 1965, the arrival of MARTA, a competing mass transit initiative, signaled the future; ATC was on its way out, and MARTA was on its way in.

MARTA arrives

MARTA began in 1965 by an act of the state legislature but did not fully see its beginning until 1971. During that period, a series of ballot referendums for regional participation of the five core counties stalled. Most of the failures came from a lack of state financial support, immediate funding, and political handicapping, in addition to a series of culture wars, including using coded language for opposition, dog whistle politics, and race-based fearmongering.

4. MARTA then and now is considered black and criminal, which hampers expansion

MARTA was, from its inception, stalled. Once MARTA was slated to be developed in the 1960s, a slew of culture wars, white flight, negative media coverage, and some very unfavorable campaigns of connecting public transit to black crime stopped the project from ever being truly effective.

Since then, regional transit services have been mostly hampered by their overall effect on what street can go on, to what extent the routes can go, and avoidance in certain parts of wealthier or more accessible neighborhoods.

MARTA’s lack of funding and autonomy started at the beginning

Despite this, MARTA received approval for the city of Atlanta, alongside Fulton and DeKalb County. Crucially, a 1968 referendum for funding failed, leading to a 1971 referendum to pass a 1% sales tax to pay for MARTA operations. Additionally, the state would not provide direct financial support.

To this day, MARTA is the only mass transit agency not to have any direct state-level funding. MARTAs funding comes with an additional set of hurdles as a state mandate that dictates the 1% sales tax must be evenly distributed between capital expenditure and operational budgets.

The result leaves MARTA unable to fund necessary initiatives or raise additional capital without state-level interference and reliant on local referendums for additional asset management.

MARTA’s actual proof of concept benefits white, affluent areas

Its role in creating economic growth by anchoring higher-density residential and commercial developments has benefited the majority white sections of Midtown and Buckhead and the northern suburbs. This anchoring of mass transit stations has also been a key to their success by bringing would-be workers and visitors to job hubs without needing a car.

5. The other transit plans that never happened.

This isn’t the first MARTA or transit map. Different ideas on what mass transit in Atlanta could look like have been floated around for decades. Here are some other mass transit ideas in Atlanta that have never or likely won’t materialize.

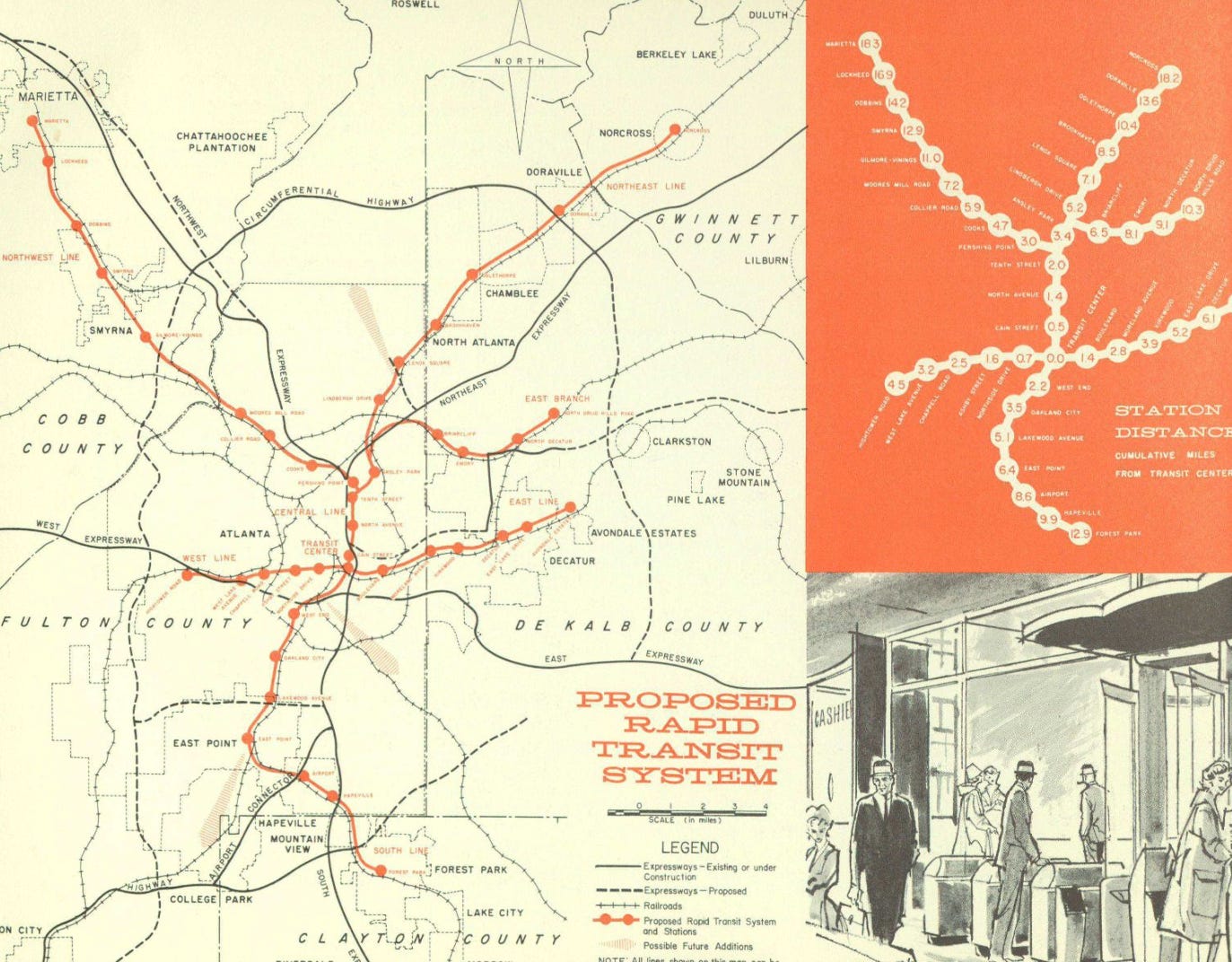

The original MARTA map

The original MARTA idea was to unite all five core counties in the 1970s. It never materialized. But other ideas of expansion further into Fulton and DeKalb counties have persisted. The original Atlanta-Fulton-DeKalb map would’ve seen a more robust transit offering in those areas.

This 1962 proposal saw extensions into smaller town centers across the metro, eventually becoming larger suburban cities, including Norcross in Gwinnett County, alongside Marietta and Smyrna in Cobb County. With never-materialized southern extensions in Hapeville, alongside Forest Park in Clayton County. The west side would get almost none of the proposed stations except for Ashby Street Station, (present-day) Joseph E. Lowery Blvd.

Meanwhile, other maps and ideas from the 1960s have surfaced. This includes a never-finished rail line in eastern DeKalb that would’ve extended from Indian Creek to Stone Mountain. As well as a long-promised but never delivered I-20 east line going into South DeKalb to current-day Stonecrest.

The Brain Train

The Brain Train is a conceptual transit project that would’ve linked the education centers of Athens (Univ of Georgia), Atlanta (GT/GSU/AUC/Emory), and Macon, Georgia (Mercer University).

Local developer Emery Morseberger is the man most associated with the plan. The plan would’ve been an anchor to make those at universities in north and central Georgia more appealing for students, faculty, and staff. The move would be closer to how Amtrak operates in the northeast, connecting elite Ivy League, liberal arts, tech schools, and community colleges.

Gwinnett County expansion in 2019 and 2020

Despite its land size (431 sq mi) and growing population (1.05 million), Gwinnett County has not allowed MARTA expansion. Gwinnett is the size of major US cities in terms of both land mass and population. As a city, Gwinnett is the 10th most populated in the US, which would be the largest in the southeast. But as of 2024, it still hasn’t expanded meaningfully with transit.

Gwinnett County is roughly the same square miles as Los Angeles (470 sq mi), the US's second most populated city. Gwinnett has a core population roughly 20% greater than Jacksonville, Florida (971,000), the 11th most populated city in the US and largest in the southeast on roughly half the square miles.

But has a transit system with as many routes (12 total) as MTA, the transit system in Macon, Georgia (11 total), a consolidated city-county roughly 15% of Gwinnett’s population at 157,000. Despite its issues, MARTA still has a daily ridership of over 90,000 passengers compared to ~5,000 for Ride Gwinnett.

There is a possibility that a third effort to bring MARTA to Gwinnett could happen this year. Despite the two previous losses, the 2020 vote was decided by less than 1,000 votes, so there is hope. If it is successful, it will likely need a better strategy for dealing with the continual fearmongering in local news, social media, YouTube, and NextDoor.

The Atlanta Street Car 2.0

The Atlanta Street Car (version 2.0) is a light rail project in downtown Atlanta that has been chided for its lack of effectiveness. The project is one of the few transit expansion ideas to happen as a byproduct of Atlanta receiving Obama-era funds during the second tenure of former mayor Kasim Reed.

The Beltline is currently in the works to expand its offering. A new extension linking the downtown streetcar to the BeltLine is in the works. The 5-stop extension is set to begin construction soon.

The Atlanta BeltLine

The Atlanta BeltLine is a mixed-use, multi-modal transit project. The BeltLine, since its arrival as a late 1990s class project from Georgia Tech student Ryan Gravel, has become Atlanta’s most transformative project since the 1996 Olympics. The still-in-the-works project has seen a 22-mile in-town loop of former rail lines be converted into a public park and walking trail.

Despite its success at generating new economic development, retail, and housing, it still has not produced any transit. Or any new meaningful connection points with MARTA buses. At the same time, some local neighbors, activist groups, and spokesmen have come out against the idea of ever building rail on the 22-mile project.

Clayton County rail

Clayton County became the third county to join MARTA officially in 2010. Since then, the county has seen bus expansion, taking over the former agency C-Tran. But despite the initial success of the expansion, rail has mostly been out of reach, alongside any further expansion of bus service throughout the county. The county is currently working on building a new BRT terminal after plans for building alongside already existing freight rail were rejected.

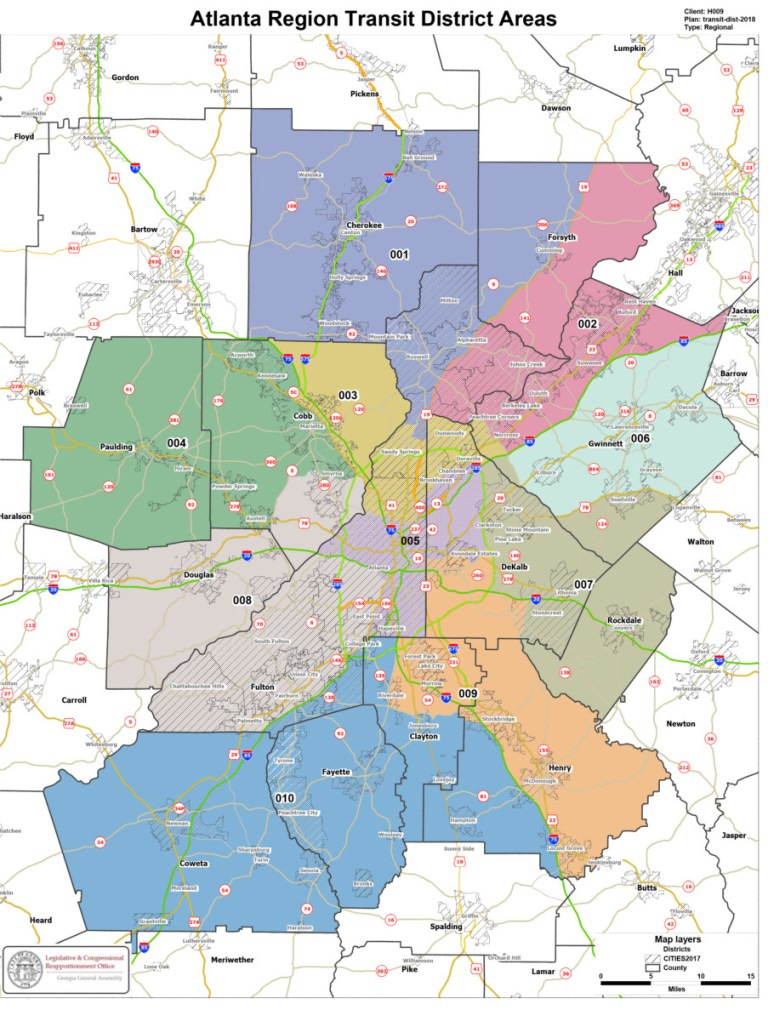

The Atlanta Transit Link (The ATL), the regional transit org that’s not producing much

The Atlanta Translink is supposed to be the region’s regional planning service. It comprised a consortium of political leaders representing 13 counties in metro Atlanta brought to life by then-outgoing Governor Nathan Deal. The idea was to build a 13-county regional planning commission to implement and develop effective multimodal transit. But it's mostly done little in the six years since its founding.

From my 2018 Saporta Report op-ed: ‘The ATL’ board needs more visionaries and fewer political appointees

The ATL represents political platitudes and a signal of a lack of care. Meanwhile, GDOT, the state’s transit board, receives an annual $2 billion allocation of funds, plus the state legislature's support, while MARTA and the ATL receive $0.

As of 2024, the ATL seems likely to fail, which could be part of the design as transit has not been a GOP priority. It’s also noteworthy that MARTA and the Atlanta Airport are the only two organizations not under GOP control. MARTA, while still attempting to keep its head above water, is still in a better current position than the ATL. If there ever were expansion, a merger of the ATL into MARTA may be the best bet forward.

The Atlanta-Chattanooga-Charlotte triangle

There have been renderings of what could be a mega-regional transit project connecting Georgia, Tennesee, and North Carolina. This southern triangle project would see an AMTRAK-type connection between Charlotte, North Carolina, Chattanooga, Tennessee, and Atlanta, Georgia.

The idea has no funding, but Charlotte, the city most compared to Atlanta, is working on expanding local and regional transit ideas.

6. The MEGA MARTA map goes viral

The map’s virality has moved in waves, first on Twitter as several different accounts and Atlanta influencers like lawyer Anthony Michael Kreis and real estate professional Donovan Reynolds began posting the image. It was then taken to new heights by the 1 million+ GA Followers account, which also posted. While on Instagram, Butter.ATL led the conversation into Millennial Atlanta. As the map continues to generate reposts and conversations, MARTA, Atlanta’s official transit organization, states the image was not real.

The map has been criticized for lacking stops in Black and low-income areas to the south and west. This is seen best on Twitter but also in the comments of several reposts on Instagram. The map also made it to Facebook, where the comments were much more civil and supportive of the idea than expected.

7. This isn’t the first Mega MARTA map

For years, people have proposed their own MARTA maps. These maps have mostly existed on personal blogs, websites, conferences, and forwarded emails for years. But since the arrival of Reddit, Twitter, and Instagram, these proposals have drawn greater attention than any other eras. Aided by an ecosystem of Urbanist websites, transit coverage, and local news op-eds, the idea of expanding MARTA has had continual success.

User-generated MARTA Maps

Over the 2010s and now 2020s, user-generated MARTA maps have gone viral. These maps posit metro Atlanta with a wider serving coverage base, going into places that have historically eschewed mass transit but sorely need it.

The Super MARTA map

This map has multiple nodes, types of rail, bus terminals, and commuter rail stations, all within the five-county core metro.

Nashville-Raleigh-Ruby Falls-Columbus-Savannah-Covington map

This map features a rail system that goes as far as Nashville, Tennessee; Raleigh, North Carolina; Columbus, Georgia; Savannah, Georgia; and Covington, Georgia. A regional map for the growing southern sunbelt.

This mega map takes several long-gestating ideas on both metro Atlanta expansion and regional expansion, merging the two together. If it were ever implemented, it would rival the current-day Boston-NYC-DC corridor of multimodal transit, which has led to further economic expansion.

Locally, the map was noticeable for how far it would connect rail between major hubs in the metro and within the state. This breaks conventions by having connection points between south metro cities such as Fayetteville and Peachtree City, connecting to southwest and southeast Georgia cities. As well as greater connection points inside I-285 and connections within Gwinnett and North Fulton.

The I-285 & MARTA loop with* the rail line to Stonecrest

This map comprises a 285-adjacent loop and several extensions of the current map. The map also features more rail in DeKalb and Gwinnett counties. This map also featured connecting rail in SW Atlanta, an area often overlooked for train and rail expansion projects.

The Better DeKalb-Fulton MARTA map

This map features a greater extension of current DeKalb MARTA lines and expansion into the densest corridors of the county. It also has a Stonecrest Station as well as a more integrated system of transit for all of the incorporated and incorporated Decatur, including Emory, North Decatur, and the DeKalb Farmer’s Market.

The image created by Jason Lathanbury went viral when it was mentioned on Curbed Atlanta (rip) in 2019. It seemed at the time as the most feasible with a price of $8 billion, or 4 years of GDOT-level funding.

The Big 11 MARTA map

This map sees a similar five-core county map but includes major hubs further into suburbs and exurbs of Cobb and Gwinnett counties. These 11 major routes would provide transit hubs in already established suburban cities, making density more of an option without sacrificing residential pushback.

This map also could be the first transit plan, including GDOT, to account for current and future growth in and around core metro cities. The map is also notable for its expansion further east into Rockdale County, southeast into Henry County, and south into Clayton and Fayette Counties. It also provides would-be service in Coweta, Paulding, and Douglas, all growing counties.

8. Conclusion

MARTA is still in 2024 and is not living up to its potential. The proliferation of user-generated maps represents a still-needed economic, infrastructure, and social need that is not being met. Mega MARTA is an idea that needs to happen before it’s too late for meaningful change. Hopefully, state leaders do.

What types of third places do you think are missing in South DeKalb?

-KJW