The Black Mecca™ - Part One

An overview of Atlanta as the Black Mecca

Welcome to my freemium newsletter by me, King Williams. A documentary filmmaker, journalist, podcast host, and author based in Atlanta, Georgia. This is a newsletter covering the hidden connections of Atlanta to everything else.

-This one is for my dad, and the conversations we’ve had on Atlanta politics.—Stay strong!

Written by King Williams

Edited by Alicia Bruce

This is the last part of a series on the future of Black Atlanta. I wanted to do a quick write-up on how Atlanta became The Black Mecca™ political and cultural center of America. What I have is this limited series and I hope you enjoy it!

I would also pair with this the following articles written or podcasts produced by me:

January 6th, 2021 is similar to Atlanta 1906 and Wilmington, NC 1898

(AUDIO) Interview with Rebecca Burns on the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot

Why do Black people vote for Democrats? - (A miniseries) -- Part One: We started as Republicans, then FDR happened

Why do Black people vote for Democrats? - Part Two: When the Democrats and Republicans switched sides

If the myth dies then what are we left with?

Despite what people in Atlanta think, Atlanta is still the gold standard of the idealism of Black hope. Whether or not the locals here believe it is a different story. Atlanta since the end of the Civil War has been seen as a beacon of hope for Black people. And in the wake of the 2020 protests, 2021 election plus demographic trends, what does it mean for Atlanta, the black mecca going forward? But to understand that we must first understand how we got here.

The Black Mecca was/is always a myth

Mec·ca (n) - a place regarded as a center for a specified group, activity, or interest.

-Merriam-Webster’s dictionary

‘The Black Mecca’ is a myth, but one created out of necessity. The idea of a ‘Black Mecca’, an American dream, where someone can buy into the notions of homeownership, middle-upper class life, or the pinnacles of business/social hierarchy has been a part of America since emancipation from slavery in the 1800s. Other cities have come and gone as the mecca, but Atlanta for the last 150+ years has existed as the mecca or one of the meccas for Black people. The construction of The black mecca narrative was one built of careful social construction, focusing on exceptionalism and collective success. Mecca existed as a fantasy due to the dire realities of life in the US.

Being a mecca is ≠ a utopia

People often confuse a mecca with a utopia. A mecca isn’t free from problems of strife, it’s that it manages to be above the strife. Utopias aren’t real, for decades Atlanta has been seen in collective memory as a utopia when that was never possible. Atlanta ain’t Wakanda because Wakanda isn’t real. But the idea of an advanced, Black-led utopia will never be lost even if the dream is. Atlanta is real, the black mecca is not.

1. Atlanta was an early Black mecca, but not the first

Cities like Wilmington, North Carolina; Tulsa, Oklahoma; Harlem, New York; the Southside of Chicago; Los Angeles, California; Washington, D.C.; and even Chatham, Ontario, Canada, have been considered a Black Mecca at some point. What’s made Atlanta different is that it’s been able to still be considered one of the mecca’s since emancipation 150 years ago. The black meccas of the 1800s were often (all-black) small towns or large, semi-autonomous sections of more established cities (Atlanta, Wilmington, NC). These towns were defined by their ability to have semi-autonomous economies, education systems (grade school and early higher ed), and some form of integration within a political system (city/county/state, federal).

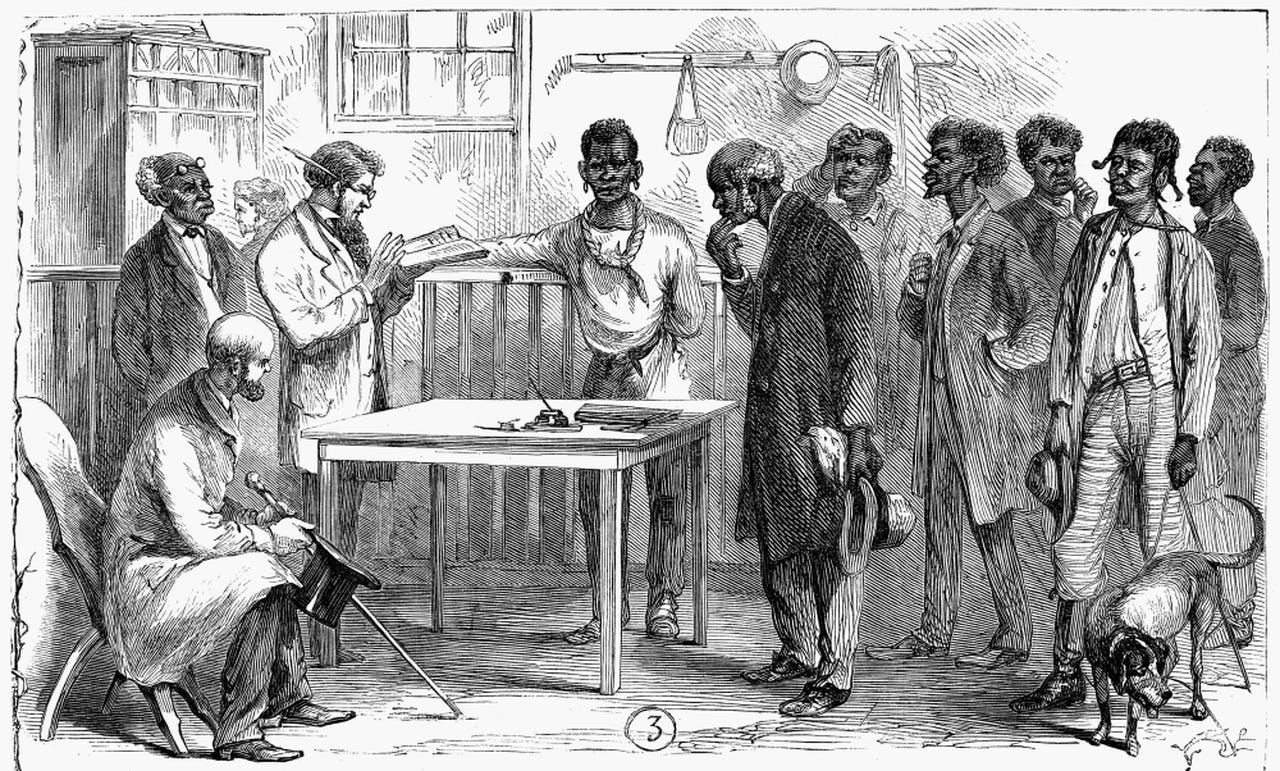

Reconstruction gave birth to the Black Mecca version 1.0

Often this political prowess came via the Reconstruction acts of the 1860s-70s, alongside their federal enforcement. This period also saw the greatest number of US Congressmen, US Senators, State Reps, and local reps in US history until a century later beginning in the 1960s. This also overlaps with the largest federal and state spending for African American initiatives such as schools, land allocations, voting protections, farming, banking, and social integration. After the abrupt end to Reconstruction in 1877, many of these early 1.0 meccas often saw violence, suspect land acquisitions, removing the political power, and a loss of financial capital.

Often due to the geographic isolation of many of these locations, by the late 1800s, most remaining Black meccas were often the (now legally) segregated sections of larger cities, i.e., Atlanta, Memphis, Wilmington, Harlem, and Washington D.C. for example. What made Atlanta different in this 1.0 era of black meccas nationwide were three important factors: 1) local prowess of black political leaders, 2) limited success in local lobbying with white lawmakers, and 3) constant yearly influx of Blacks to the city.

2. Atlanta as the Black Mecca version 1.0

The post-Reconstruction Atlanta era included the immediate disenfranchisement of Black voters. Black political progress was often in direct opposition to white suppression laws.

The post-Reconstruction era Atlanta

Black political leadership in Atlanta also often represented Black Georgia. Atlanta was founded in 1847, burned down by 1864, then became the state capitol in 1868. The city became the statewide lobbying point that exists for all Georgians. As a result, often the efforts of local Black Atlanta politicos had to also consider the larger implications of its effects on Georgians.

The limited success of Reconstruction in the 1860s-70s provided the climate for this development. Atlanta succeeded in the Reconstruction and in the post-Reconstruction south because there was such a critical mass of Blacks living in the city, often from smaller towns throughout the state and deep south, who were able to access the city because of the train routes. Issues statewide could be heard, then spread easily from the city amongst the people, the black press, and black leadership. Atlanta became the launching pad for grievances for Black Georgia.

Late 1800s Black political leadership in Atlanta

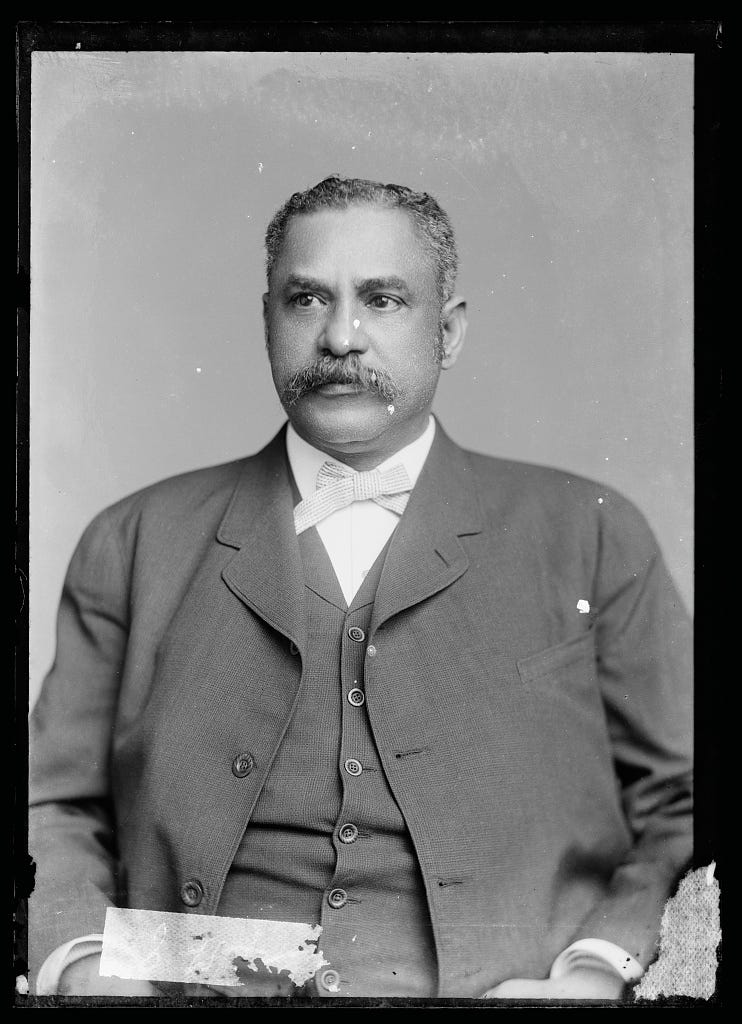

Henry Allen Rucker’s run as one of the most important Black political figures of the late 1890s-1910s is one of the foundational pieces of the early stage Black Atlanta.

Rucker was a man who was born into slavery in 1852, who after the death of his master, relocated to Atlanta at the end of the Civil War. From there he would work his way up to opening up his own barbershop that catered to elite white clientele. Allen would also attend Atlanta University before becoming a teacher in the Atlanta public school system, all by the 1870s. In the 1880s Rucker began to become more involved in city politics. He also worked his way into becoming a tax collector, becoming one of the longest-tenured and most senior in the state of Georgia at that point in time. This unusual amount of access to a state job with a degree of real power garnered a decent amount of political heft.

The other Black leaders in Atlanta

There were several Black leaders in Atlanta in the late 1800s, while Rucker is the most prominent, the Black Atlanta establishment was almost exclusively male, and of decent social standing within the Black community Atlanta large. Jackson McHenry, Howard Horton, R. J. Henry, Rufus King, A.W. Burnett, J.W. Palmer, and also W.A. Pledger, H.A. Rucker, C.C. Wimbish, Smith Easley, Reverend W.J. Gaines, Moses Bentley, and A. Graves. Atlanta’s Black leadership at the time was also heavily invested in the Republican Party at the time as the GOP largely left the south after the end of Reconstruction, then in a larger amount after the various racial massacres that would occur from the 1880s-1920s.

Read: Why do Black people vote for Democrats? - (A miniseries) -- Part One: We started as Republicans, then FDR happened

The Big Three - Henry Allen Rucker, Judson Whitlocke Lyons, and John H. Deveaux

Rucker alongside two other Black men, Judson Whitlocke Lyons and John H. Deveaux became known as ‘the big three. But also there were others including Rucker’s rival, Benjamin Jefferson Davis Sr., aka ‘Big Ben’, he was the father of Benjamin Davis Jr. (b. 1903). Big Ben Davis who would later start the negro paper The Atlanta Independent. Rucker, Davis, Deveaux, and Lyons were all known as ‘race men’, men who had more social and economic success than most of their peers black or white, but fervently worked on issues regarding the Black community. Rucker even by 1904 had his own building built which would work on issues for the Republican Party as well as other issues affecting the Black community in Atlanta.

These men sought to expand the political agency of Atlanta during an era where political autonomy was rapidly eroding across the country. This included maintaining the presence of the Republican Party in the state of Georgia, which had mostly been gone from prominence after the end of Reconstruction. As a result, Rucker was appointed as a delegate to the national Republican National Convention. By 1896 Rucker was advocating for presidential candidate William McKinley, who would become the 25th President of the United States that same year. It was KLB-Biden a century earlier.

Black Atlanta’s limited political success of the late 1800s

Atlanta’s growing political heft in city/state politics in combination with being the reason for the Republican Party having presence remaining within the state in the years after Reconstruction, gave Atlanta more political prominence. This period had many of the hallmarks of what we associate with Atlanta’s Black political leadership—an uneasy relation of Black elites to white politicians, a small group of prominent Black men opting out of political power, focusing on personal financial success, and a consistent effort to remove Blacks from the voter rolls.

Often during the election season, some Black Atlantans would openly attempt at courting members of the opposing party, which at that time was the Democratic Party, with the hopes of gaining more inroads of wider opportunities in the city. Usually, this was left on deaf ears but on some occasions, Atlanta’s southern White Democrats would hear or give small token claims while on the campaign trail of addressing ‘negro needs’. This included an 1890 all-Black ticket for city elections, which was soundly defeated, then led to a very tough crackdown on Black political participation. Despite the loss, Atlanta’s political leaders were able to retain national prominence with the Republican Party, while on the local leadership level, the city was able to get some gains, even though post-the 1906 gubernatorial race and the 1906 racial massacre, they would largely be wiped away by the governorship of Hoke Smith.

3. Booker T. Washington vs W.E.B. DuBois and ‘The Atlanta Compromise’

The environment of the late 1800s and early 1900s saw an explosion of race-related violence and racial terrorism. During that time period, two of the most important black leaders, Booker T. Washington (b. 1856) and W.E.B. DuBois (b. 1868) emerged. These men plus Ida B. Wells became national black leaders during this time period.

Washington and DuBois offered two fundamentally different visions of Black America.

Booker T. Washington was arguably the most important Black political leader in the country by the late 1800s and the most well-known. Washington was president and founder of Tuskeegee University in Alabama, a school that had just opened in 1881. While DuBois, 12 years younger, would be become the first Black person to earn his Ph.D. from Harvard while also developing the modern framing of discipline now known as sociology as well as being a founding member of both the Niagra Movement, which birthed the NAACP. Both men represented two distinct points of reference that are now canonical across the disciplines of Africana/ African American studies - inclusion versus isolation.

Booker T. Washington (1856-1915)

In the Washington version, the achievement of African Americans would come through self-sufficiency, economic independence, and eventual acceptance with white America. He also advocated against political engagement or breaking social order, with the idea that over time the eventual white American acceptance would lead to full inclusion. Washington also wasn’t necessarily interested in integration with white Americans, which also brought even more support to his causes.

Washington due to his ideas, approach to race and political issues would find a large base of white and black supporters. Especially among white business owners who found his less threatening version of inclusion, more palpable. While many African Americans also found this more practical as racial acts of terrorism, an abundance of new Jim Crow laws, the birth of convict leasing + the rise of American industrial prisons, were almost exclusively targeting them throughout the south. Washington’s adherence to obeying white authority made him a prototype of what is now considered white political tokenism, by finding a black figure who espouses or believes in the white social order/ideology. But this did not make Washington an ‘Uncle Tom’ as his points for self-sufficiency and autonomy from whites was not based on an inferiority complex nor Stockholm Syndrome.

W.E.B. DuBois (1868-1963)

While in the DuBois version, he offered a more direct, antagonistic relationship towards achieving success. DuBois believed in immediate integration and inclusion across the spectrum in the US. DuBois was vehemently against the idea of waiting on white acceptance in any capacity unless it lead to direct full citizenship. DuBois due to both his age, upbringing would later be characterized as the beginning of Black radicalism (not liberalism), in the US. DuBois’s thoughts and his work on studying Black life via sociology did gain him a base of liberal and northern white supporters. These supporters also aided in the advancement of DuBois’s ideas to non-southern white audiences across the country. DuBois also was an adherent to the notion of a ‘talented tenth’ a special group of Black leaders who could elevate the entire Black community through their knowledge, leadership, and networks—political and economic.

In both cases, these men have historically been mischaracterized, but both were in full support of African American self-sufficiency, education, Black safety, anti-racism, and autonomy. On the day of September 18th, 1895 in Atlanta, Georgia, the two men would become lifelong foes.

The Atlanta Compromise Speech of 1895

Booker T. Washington was invited to speak at the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition held at Piedmont Park. Washington was there to give the speech to white political, business, and social leaders who’d become concerned about a growing black middle-upper class. The speech was also aimed at calming mounting anger at a new base of Black workers who at the time we being used as an exploit to undercut white laborers.

In his speech, Washington stated that Blacks would not seek out the right to vote, tolerate segregation, endure discrimination, and not seek retribution against violent acts. In return, that white leaders should support paying for Blacks to receive a basic education, in particular vocational and industrial training, to be better workers. This speech was supported by the whites in attendance that day but not DuBois, who would get word of the speech. Washington’s positioning is now considered to be what is known as accommodationism amongst Africana/African American Studies scholars. DuBois called the speech ‘The Atlanta Compromise’ and the rivalry was on from then until the death of Washington in 1915. DuBois would move to Atlanta in 1897 to found the sociology department at Clark College (now Clark-Atlanta University). DuBois’s move to Clark College also signaled a new step in the prominence of Black Atlanta, the role of its colleges and universities. A move that would have immediate effects on the city at large, as well as aid in the eventual formation of the NAACP.