The Campbellton Road MARTA controversy explained

Misinformation, misdirection, but not misappropriation of funds

Welcome to my newsletter by me, King Williams. A documentary filmmaker, journalist, podcast host, and author based in Atlanta, Georgia. This is a newsletter covering the hidden connections of Atlanta to everything else.

I recently wrote an editorial for DeKalb-centric news site, Decaturish on a recent issue regarding a proposed highway expansion at I-285 and I-20 East. The proposed $650 million renovation and expansion at I-285 and I-20 East by the Georgia Department of Transportation (GDOT) is part of a long history of South DeKalb continually getting the short end of the stick regarding rail service in the area.

I suggest you read that editorial in combination with this article.

5 Biggest takeaways from that article:

DeKalb has its county commissioners and US Congressman Hank Johnson on board with more transit support.

South DeKalb, for years, has been waiting on its rail service. Campbellton Road, an area with similar demographics is facing a similar situation.

Emory has been working on a plan for decades on having transit, eventually leaving incorporated DeKalb for the city of Atlanta in 2018 over transit.

MARTA’s financial standing long-term due to ridership loss is a factor.

South DeKalb has two plans that could use a boost of funds to make a reality.

1. The controversy on the Campbellton Road BRT project

In a surprise move, a very public schism emerged with MARTA and several elected officials over a proposed Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) project slated to come to Campbellton Road. The schism has erupted at the intersection of two Atlanta City Council members, Councilwoman Marci Overstreet and Councilman Antonio Lewis, Buckhead secession leader Bill White, and MARTA.

It was Lewis’s Instagram post that got things rolling online, in that post, Lewis gave information for a town hall to be held on Tuesday, February 8th, regarding the change in transit options for the Campbellton Road corridor. Since that post, several people across the Atlanta social verse have criticized MARTA for backing out of the proposed light rail on Campbellton Road. A move that has elicited criticism from current city council members and former Mayor Keshia Lance Bottoms.

1b. MARTA vs Marci Overstreet

Startingly, MARTA went to Twitter to directly respond to the allegations. MARTA chose to respond directly to Councilwoman Overstreet, pointing out her support of the project being BRT, as well as posting a video of her saying this.

In addition, MARTA has released the Campbellton Outreach Summary as well as a series of previous meetings including releasing time-stamped statements of Overstreet being in support of a BRT option. This is a move aimed at highlighting a potential contradiction of Overstreet regarding her claims of being continually pro-LRT only for Campbellton Road.

1c. Bill White’s post escalated things

In a recent post by the Instagram account ATLScoop, Bill White, the Buckhead secessionist leader reposted with a comment on his account and his IG Story. White directly insinuated that former MARTA CEO Jeff Parker’s suicide was a result of misappropriating funds. This caused councilwoman Amir Farohki (District 2) to directly state that this post by Bill White was not only wrong but also in bad taste. Even since the reporting of Parker’s death a few weeks ago, social media chatter has had a small amount of similar thinking related to this passing.

1d. MARTA did NOT steal money from Campbellton Road LRT

MARTA did not steal money, nor was the death of Jeffery Parker related. The ‘stolen money’ for Campbellton Road did not happen. The claim of theft came from an article from a February 7th, 1380 WAOK AM entitled MARTA Accused of ‘Stealing’ Two Hundred Million Dollars From Black Community. MARTA is claiming as a result of their 2021 outreach efforts that the community narrowly voted in favor of BRT over LRT. MARTA claims that the BRT version of the project is estimated at $130 million dollars, $187 million less than the LRT version.

The money in question is part of a FUTURE allocation of local tax funds for the More MARTA campaign that was passed in 2016. As a result of the potential Campbellton Road BRT project, a potential reallocation of funds, funds which could (but not set in stone) remain to secondary projects within that area OR be reallocated to other More MARTA projects.

The statements of this claim for ‘stolen’ money have come from Councilwoman Overstreet herself who said it at Tuesday’s town hall. MARTA as a result has released a statement:

MARTA is extremely disappointed with how the situation regarding the Campbellton Corridor project has unfolded and the negative and inflammatory tone of the conversation surrounding the proposed transit mode. Councilmember Overstreet has been closely involved with this project since its inception and is fully aware that light rail was never promised in this corridor. In fact, she has stated publicly that her constituents aren’t interested in light rail. She has also been publicly supportive of BRT and its benefits…

…For Councilmember Overstreet and others to suggest MARTA is “stealing” money from Southwest Atlanta and the Campbellton Corridor project is absurd and false. The More MARTA Program does not set aside a specific amount of money for specific Council Districts, rather, the program expands the transit system for the benefit of all Atlantans. It is irresponsible to suggest that MARTA and the City of Atlanta teams that jointly administer the More MARTA Program have been anything but responsible stewards of that funding.

We look forward to less inflammatory rhetoric and more productive discussion in the future.

The statements have also been echoed by Councilman Antonio Lewis and 1380 WAOK radio host Rashad Richey. Since then, the post has been circulating across local Atlanta traditional media outlets and social media accounts. The accusations, in combination with the town hall, public perception of where the funds are or why the Campbellton Road’s project has been ‘downgraded’ to a BRT project remain. These sentiments were echoed at the MARTA townhall that had Overstreet in attendance.

The More MARTA campaign of 2016

2016’s More MARTA campaign saw a majority of the city of Atlanta residents vote for the first massive in-town transit expansion in years. The vote would be for a half-penny sales tax that would generate an additional $2.7 billion dollars of funding for new transit projects. The project list includes investment in missing middle transit corridors within the city, including places like Campbellton Road.

Note, this expansion aids in becoming an adjacent connection point to projects such as the Atlanta BeltLine, current MARTA bus/rail service, and the Atlanta Streetcar. This More MARTA plan is built for the anticipated 2.9 million people who will call metro Atlanta home by 2050, including an estimated 600,000+ in-town residents.

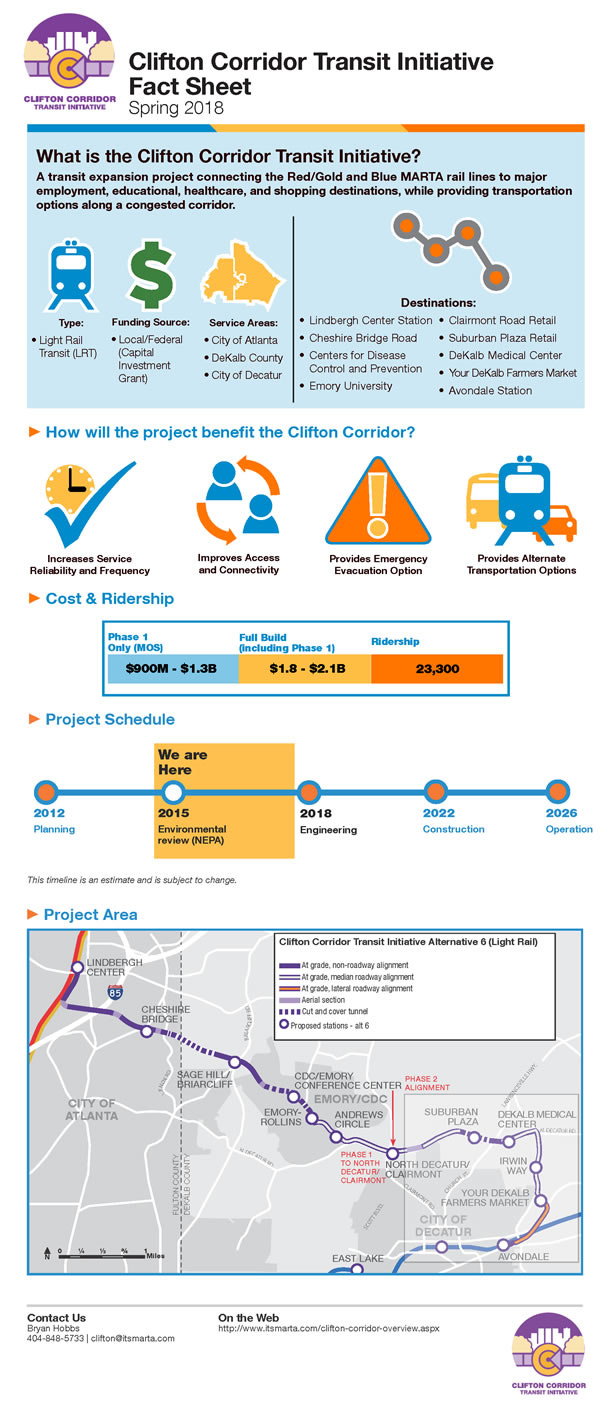

2. Emory’s LRT vs Campbellton LRT

One of the biggest criticisms of MARTA’s bus for BRT has been the comparison of Emory’s LRT plans to that of Campbellton Road’s LRT plans. MARTA’s push for BRT instead of LRT on Campbellton Road is largely for the costs savings. MARTA estimates a BRT system on Campbellton Road would cost $130 million versus an estimated $317 million for an LRT system. Critics of the deal have decried why has Emory, a former unincorporated DeKalb region that just entered the city limits in 2018 is getting a perceived funding priority over Campbellton Road.

Density

Both projects were proposed as $300 million dollar LRT projects in the initial 2016 More MARTA campaign, including its updated 2018 study of the plan. For Campbellton Road, the issue outside of costs would be density and potential ridership. The Campbellton Road area has an estimated 7,900 residents in the area compared to the 6,400 in Emory.

But two important caveats: first, Emory is in a shorter, much denser residential/commercial corridor making any road expansion, especially for BRT unlikely, but not impossible. Second, Campbellton Road is a much longer corridor, with far less density than Emory despite having more residents — 7,900 for Campbellton Road vs 6,000 for Emory.

The Clifton Road Corridor’s density

Emory’s corridor, the Clifton Road corridor is particularly dense. Emory’s density argument is primarily due to the number of direct/indirect participants of the Emory University, Emory Hospital, and CDC corridor of workers. Emory University comes with a built-in base of 7,000+ students, nearly 3,000 on-campus faculty and staff, over 2,700 at Emory hospital, not to mention the nearly 15,000 employees at the CDC next door. Emory also has a constant built-in network of employees via its massive health care system, the metro area’s largest employer three years running.

Emory’s landmass sits directly next to three additional dense corridors:

The eastside: Tucker, Clarkston (the densest city in the entire state), and Decatur (both incorporated+unicorporated).

To the west: Atlanta, this includes Druid Hills, Morningside, East Atlanta (not the village) + Moreland Avenue corridor, Brookhaven, Buckhead, and Buford Highway.

To the south: Unincorporated Decatur/southwestern DeKalb Count including East Lake and Kirkwood.

MARTA believes that this corridor could be used daily by 21,000+ residents. Making it a more likely candidate for needed LRT service. Road expansions in this area are nearly impossible without extreme costs and years of development.

2b. Emory’s LRT

Emory’s LRT began in 2012, 6 years before it joined the city of Atlanta. Emory filed for annexation from DeKalb County into the city of Atlanta in 2017, then joined on January 1st, 2018. Campbellton Rd has been in Atlanta, since the beginning of Atlanta.

Emory’s LRT is too important to mess up

Emory’s LRT was one of the impetus for leaving for Atlanta in the first place. There was no way then or now, that the city would’ve not made sure MARTA will give them their LRT project. Additionally, if Atlanta has to expand further into the county as a hedge against another cityhood initiative, the proposed City of DeKalb, Emory’s LRT transit line is of even greater importance. The Emory LRT would then serve as a connection point of more importance into the newly established eastern end of the city. An eastern end that would go potentially as far as Lithonia and Rockdale county, with a corridor of nearly 300,000 residents—60% of the current population of the city of Atlanta.

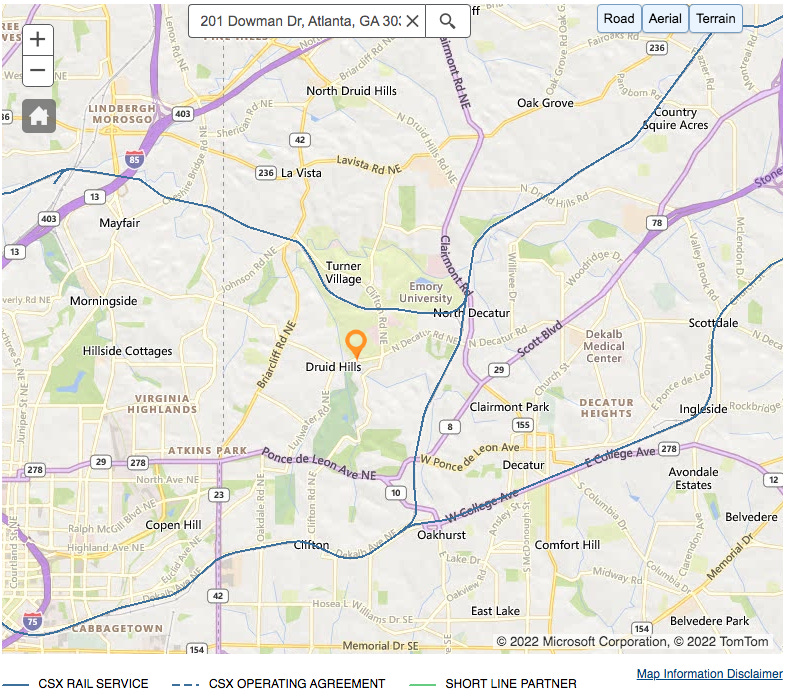

Because of Emory’s newcomer status, its preliminary work on assessing the land via the Clifton Corridor plan, and its wealthier cohort of residents, it’s unlikely any city mayor would do anything to stifle a relationship this young. But this will contain a potential dispute with the right of way with CSX Railroad which has an intersecting railway that cuts directly through Emory University and that section of North Decatur/Atlanta.

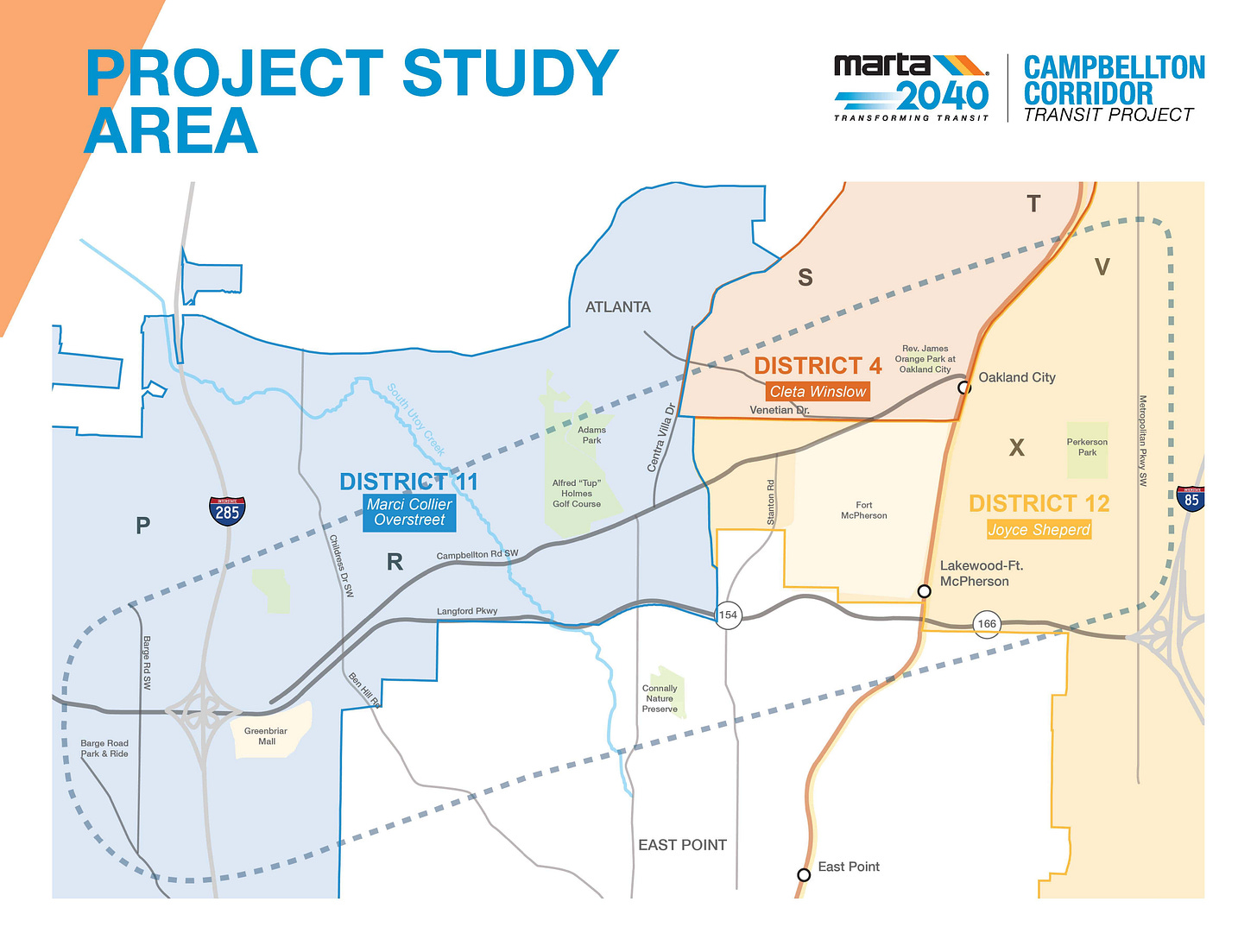

2c. Campbellton Road LRT

The proposed LRT would be bisecting through several city councilpersons districts. The Campbellton Road corridor project resides in several majority-Black areas on the westside of Atlanta. Those districts, 11, 4, and 12 all reside in various gentrifying sections of the westside, intersecting with some of the poorest parts of the city.

MARTA’s 2020 summary on the project can be seen here.

The Campbellton Road TAD

In 2006, the Campbellton Road Tax Allocation District (TAD) was created with the help of Invest Atlanta. The Campbellton Road TAD was enacted as a way to jumpstart economic development in the area. Since then, Campbellton Road has seen limited ancillary economic investment, when compared to the corridors of Bankhead, the West End, and Marietta Street—actively being rebranded as ‘West Midtown’.

The Campbellton Road TAD vs South DeKalb’s TBD plans

Campbellton Road, like South DeKalb, are majority Black areas that have been mostly avoided by any major economic development projects. Both South DeKalb and Campbellton Road are areas dealing with early-stage residential gentrification. In addition to a large cohort of older, mostly middle-class Black homeowners plus poorer black renters. Unlike South DeKalb, the Campbellton Road TAD has gotten off of the ground, is a part of a larger system expansion with the funds to build now. While South DeKalb is still TBD, despite the existing plans of Memorial Drive revitalization plan, MARTA’s own I-20 East corridor project, and DeKalb’s master plan.

3. BRT vs LRT

The Campbellton Road Corridor Project has sought public comment since last summer on the costs associated with becoming a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system versus a Light Rapid Transit system (LRT).

The price discrepancy that was cited in Councilman Lewis’s post comes from a 1380 WAOK AM article on the issue. The costs of BRT are roughly $130m for two dedicated bus lanes, versus $317m for LRT, including a new hub for the train.

3b. Which is better BRT or LRT?

LRT and BRT are not in competition with each other, costs and local priorities are. Several cities across the world have both, operating as a cost-efficient middle ground to heavy rail, highways, or both. BRT and LRT are the biggest in Europe and South America. South America is being most associated with success in BRT but also has several successful overhead tram (cable car) initiatives as well.

3b. What size is right for BRT vs LRT

BRT vs LRT is a debate that has happened a lot in cities over the years as it relates to creating affordable transit options. The choice of BRT vs LRT often arises when a local municipality is deciding on what type of mass transit option would be best suited based on location and population. Often between a non-heavy rail (ex: LRT), non-road expanding (ex: BRT), bike shares, or non-highway transit options.

The BRT vs LRT is most prevalent in midsized and small cities. With the definition of ‘small’ and ‘midsize’ being relative. ‘Small’ city definitions are for cities between 100,000-499,999 residents and ‘midsized’ are between 500,000-999,999. While big cities are typically above 1 million residents and megacities are above 10 million residents. When cities are above 1 million residents, when considering mass transit, it’s usually in combination with heavy rail + either BRT, LRT, bike share, or a combination.

3c. BRT or LRT’s other factors

Often this planning of BRT/LRT will also weigh in how a city’s perspective transit ridership would reach. Three big factors (outside of price and construction costs) of BRT/LRT development plans include:

Prospective riders from neighboring edge cities (ex: city of New Jersey PATH)

Subregions within a city (ex: Los Angeles’s Metro Rail)

‘Spur development’ where a BRT or LRT project brings secondary economic development to an area (ex: Portland’s light rail system)

Sprawl and density within a city and/or metro (ex: Dallas light rail system)

In deciding BRT vs LRT, often it’s a matter of local priorities. Often an LRT system is a much better gauge of long-term interest in revitalization, where BRT is often seen as a means of transport. This isn’t to say BRT is not an economic engine, it definitely is, but especially in America, it’s hard to have people have enthusiasm for the bus.

The opportunity costs of BRT and LRT

LRT and BRT are not in competition with each other, costs and local priorities are. Several cities across the world have both, operating as a cost-efficient middle ground to heavy rail, highways, or both. BRT and LRT are the biggest in Europe and South America. South America is being most associated with success in BRT but also has several successful overhead tram (cable car) initiatives as well.

A) The + and - of LRT

The positives (+) of LRT

LRT is still a train, albeit not as complicated as a subway or freight train. All trains work on fixed lanes, often in segregated portions of cities, towns, and countries. Trains can gain higher speeds but cannot operate outside of the fixed routes. Passenger trains like subways or light rail work best in high volume/high density commercial or residential districts, as well as in high-capacity venues like an airport.

The negatives (-) of LRT

LRT requires purchasing more units to offset a loss of vehicles during maintenance. LRT can often move up and down in need of attaching units. Also, most LRT vehicles often have dual-end cabs which allow for trains to run in reverse. LRT can only be moved if there are cables and/or tracks to facilitate a move.

Power sources of LRT

Most light rail is powered by electricity often through overhead wires (ex: San Francisco cable cars) or a third rail (ex: The Syndey Light Rail Network). Or in some cases a combination like several of Japan’s bullet trains which operate with both an overhead wire and backup battery. Currently, several counties and companies are working on a fully electric, battery-powered LRT system. The biggest issues have been costs, manufacturing, and overall distance traveled. While some countries such as England and Ireland have used diesel-powered batteries off-and-on since the 1900s.

B) The + and - of BRT

BRT is often a choice of cities because of the costs and flexibility it allows. In many cases, BRT and LRT carry the same amount of passengers, but their impacts differ. LRT is often used as an anchor for new ancillary economic development, while BRT can do the same, in the US it’s been a harder time to do so.

The positives (+) of BRT

BRT is more flexible in its use, allowing for immediate changes in routes, stops, and rapid deployment of vehicles to address new needs. Buses are also easier to locate parts for maintenance and vendors to provide servicing when compared to LRT. BRT’s flexibility translates to a variety of designs in transport centers, storage depots, and creating dedicated lanes, often being done for a fraction of the costs needed to do the same for LRT. Additionally, BRT often does not require a new skill set for drivers, maintenance workers, and specialized repairs when compared to LRT.

The negatives (-) of BRT

BRT is still a bus. Buses increase in cost as ridership grows. Buses have shorter vehicle lifetimes because of the internal combustion engines used to power them. BRT often requires more maintenance because of the wear and tear associated with vehicles. BRT also is most efficient when given a dedicated lane, which in urban areas or on highways competes with individual drivers. BRT also suffers in public opinion, especially when compared to other mass transit options such as heavy rail and LRT.

Some physical problems with BRT

But the biggest is the rolling resistance of the vehicle while in motion. The main contributor to rolling resistance is the process known as hysteresis. Hysteresis is the energy loss that occurs as a tire rolls throughout its path. The energy loss of this must be overcome by the vehicle's engine, which results in wasted fuel, fuel that must constantly be replenished in a combustible engine. Additionally buses suffer from aerodynamic drag while in motion. In addition to tires being subject to the laws of slip dynamics including micro-slippage and various forms of deformation.

Power sources of BRT

Today most BRT systems are still powered by diesel engines, using what is known as diesel multiple units (DMUs). Due to the relative ease and costs of acquiring diesel, this has been the de facto power source of most buses for decades. But over the last twenty years, there has been a greater push to alternative and hybrid powering of busses. These include electricity-powered, natural gas, hydrogen-powered, or a combination of the aforementioned power sources. MARTA has used a hybrid approach to its fleet of vehicles, including using natural gas-powered vehicles in its fleet. The agency in 2021 claimed that 3/4ths of its entire fleet of buses use compressed natural gas, with the goal of replacing 6 older diesel-powered engines with fully electric vehicles.

4. The problem with the ‘you don’t have the density’ for LRT

Often critics of the idea of South DeKalb rail service cite the lack of high-density corridors when compared to the northern end of the county. The initial development of these transit stations came about beginning in the 1970s when the county’s population was substantially less dense than South DeKalb. MARTA’s northern stations allowed for the continued commercial development of Midtown, Buckhead, and the growing suburbs at the expense of nothing for South DeKalb or South Fulton. Which coincidentally corresponded to the extended patterns of residential white flight outside of the city.

In Atlanta, the initial penny sales tax of MARTA facilitated the growth of the northern Fulton and DeKalb suburbs. Dunwoody/Perimeter, Chamblee, Brookhaven, North Springs, Sandy Springs, were all less dense spaces before the start of MARTA’s construction. It’s part of the reason why South DeKalb residents cite the importance of rail in anchoring long-term economic growth.

5. Rail + bus service anchored the growth of metro Atlanta

The biggest opportunities for LRT come after the track is formed. LRT and heavy rail can be huge anchors for long-term economic growth. The growth of Atlanta’s two most important economic regions Midtown and Buckhead happened because of its anchoring transit-oriented developments (TOD). Midtown is the biggest benefactor of having mass transit. The area now called Midtown was the site of the first gentrification efforts in the city in the 1970s. Much of that residential gentrification occurring around Piedmont Park and commercial gentrification along Peachtree Street.

MARTA rail anchored economic growth

Following these efforts were the 1980s eras of heavy rails stations opening. DeKalb County actually received many of the earliest stations in 1979. This included Avondale, Decatur, East Lake, and Edgewood/Candler Park. Stone Mountain was noticeably not on that list due to its own intersection of white flight further eastward in DeKalb and a stand against the feared ‘black crime’ associated with public transit.

In Midtown, this included the opening of the North Avenue train station in 1981, alongside the Midtown and Arts Center stations in 1982. For Buckhead, both Lenox and Lindbergh debuted in 1984, Buckhead station in 1996. For northern DeKalb, Chamblee opened in 1987, Doraville opened in 1992, and Dunwoody in 1996. In North Fulton, this saw Sandy Springs gain three stations within a four-year period, Medical Center in 1996, in addition to both North Springs and Sandy Springs in 2000.

6. Cobb County is attempting to transit on the ballot in November

Cobb County Chairwoman Lisa Cupid has been working to get mass transit expansion to Cobb voters this November. Cupid has been working over the last year to get the necessary frameworks in place to get mass transit to Cobb. Cupid et al, have been hosting town halls with the most recent being in November of 2021.

Cupid and Cobb transit advocates are citing the passage of HB930, the metro regional transit initiative that brought about The Atlanta Region-Transit Link Authority (The ATL) and HB170, which allows for municipalities to spend up to 1% of revenues for 5 years to fund surface projects, as the reason for pushing now for transit. Should that happen, it would be the funding framework that would anchor this potential transit plan for the county. Cobb voters in 2020 already passed a SPLOST referendum which would allow for funding for county agencies including transportation.

6b. Cobb needs transit

Cobb currently has Cobb Link, a much smaller, transit system that is woefully not as expansive as MARTA. This comes as a problem, as Cobb is projected to keep growing, which should be around 1 million residents by 2050. This is also with the additional problem of cityhood efforts in four cities, which could see an abrupt halting to the plans, especially if it can’t get on the ballot in November. As for why Cobb still doesn’t have mass transit, TL/DR: racism + generations of equating crime with transit. I would recommend Atlanta Magazines, Where It All Went Wrong article.

I hope this helps add a little understanding to the BRT vs LRT controversy. - KJW