White Flight in Atlanta and The New Voting Power in Georgia

Why implying 'the suburbs' is too limiting when explaining Biden's win in Georgia

Welcome to my newsletter by me, King Williams. A documentary filmmaker, journalist, podcast host, and author based in Atlanta, Georgia.

This is a newsletter covering the hidden connections of Atlanta to everything else.

Written by King Williams

Edited by Alicia Bruce

How White Flight led to a Biden win in Georgia

Joe Biden’s victory over current President Donald Trump earlier this month was a nail-biting and invigorating election for both political parties.

However, Biden’s win came a few electoral cycles earlier than expected. The story of Biden’s campaign has been its ability to win in the suburbs. However, the Atlanta suburbs of 2020 are much different from those suburbs of 1992, which was the last time Georgia elected a Democrat for president.

This regional expansion exists due to decades of white flight further and further out of the city core. Each expansion has provided a new threat to the established rule of the Republican party. White flight built the modern metro Atlanta and the modern conservative movement. But now, it may have built the basis for the next Democratic movement.

I. White Flight

White Flight is the phenomenon of White residents leading residential areas after the population becomes too non-white or threatens White sensibilities. White Flight in the US has moved in cycles. Initially, it started during the New Deal era of the 1930s and expanded tremendously after the end of World War II in the 1940s.

During this period, the US government explicitly paid for segregated communities. The federal government, via the New Deal programs, gave money to real estate developers to build White-only communities, gave financing for homes explicitly for White people, developed public housing initially for whites-only, and backed private homeowner loans for White people.

This was aided by the banks, financial firms, and private real estate markets explicitly discriminating against potential Black homeowners. Private real estate agents often steered potential Black homeowners into other segregated areas, and when they were steered into White areas, it was often for the purpose of blockbusting.

African American homeowners in these scenarios were often overcharged for homes in White neighborhoods, which at the same time resulted in White homeowners quickly losing value in their homes, which would lead to them selling their homes. These sales (often at a loss for White homeowners) would then be made by the same real estate agents who would then sell to other prospective African American homebuyers but then sell White homeowners newer, segregated properties in the suburbs. As a result, real estate agents developed a uniform system to assess whether or not a neighborhood was White—redlining.

Redlining and Black neighborhoods

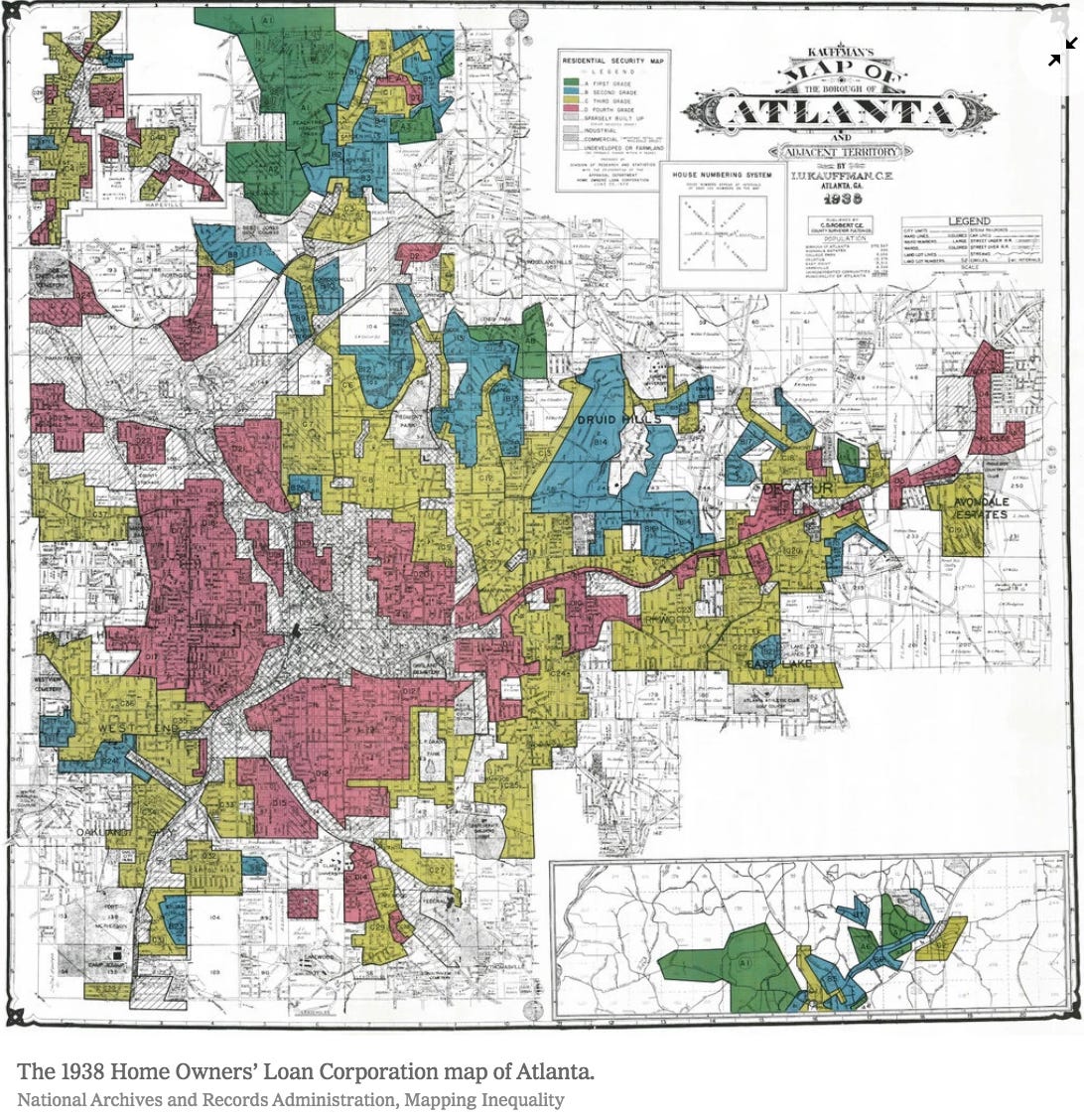

Redlining is a formalized practice of residential discrimination, dating to the 1930s but existing before that informally.

In the 1930s, a new government agency was birthed out of the stock market crash of 1929. It was known as the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC). The HOLC’s sole purpose was to help spur and maintain homeownership, as many homeowners lost their properties due to the Great Depression. The HOLC was responsible for categorizing risk regarding homeownership in addition to being responsible for reinvigorating the national housing market. These HOLC-backed loans were given to White Americans and the real estate companies who would be servicing them.

These determinants of who were potentially qualified safe risks (White people), were already de facto practices of segregation by White-owned commercial real estate companies, banks, and private lenders before the HOLC was formed. These lenders often purposely excluded African Americans, even when they had more money to pay for properties. With the government now in the private housing market due to the New Deal, these practices became de jure housing policy.

II. Atlanta and redlining

In Atlanta, this meant that all of the African-American residential areas were at risk regardless of income, status, education, or occupation.

Colors on map: A (Green) = Best, B (Blue) = Still Desirable, C (Yellow) = Definitely Declining, D (Red) = Hazardous

The neighborhoods that overwhelmingly received the worst grades were the ones with the highest share of minorities, especially Black residents. Grade ‘D’ locations were often Black or minority-only neighborhoods, while grade ‘C’ were neighborhoods experiencing a decline in white residents. These low grades gave cover for segregationists and anti-integrationists within both government and the private market to legally restrict funds needed to improve Black America’s housing stock.

III. The Atlanta metro area’s initial expansion was because of White Flight

The period of the 1960s is the development of what we come to know as metro Atlanta. The 1960s was the last holding period of the white majority for Atlanta, as many whites in this period started moving further north into parts of Buckhead and North Atlanta. Some just moved into small towns like Decatur, north DeKalb County (Dunwoody), and some into newly created suburbs outside the city limits.

Many of these white Atlantans were people who either shunned looming ‘forced integration’ of Atlanta’s public spaces and schools, while others were turned off by the burgeoning civil rights movement, in addition to the spreading out of the Black upper class into neighborhoods such as Cascade and the West End. With the availability of affordable, socially segregated, and newly constructed homes in the newly constructed burbs, the incentives for leaving for white Atlantans grew by the day.

White Atlantans left the city in disarray, then got out of town, literally

In 1960, Atlanta reached a peak white population of roughly 300,000, with the residential population comprising nearly 62% of all residents. However, the resulting one-two punch of integration and the peaking of the civil rights movement in the early 1960s caused the white population to decline precipitously over the next decade. Atlanta, by 1970, was 51% Black. By 1980, nearly 67% of Blacks remained above 60% until the mid-2000s.

As whites abandoned the city of Atlanta, the ethos of many of its suburban developments was to provide a newer safe haven of self-segregation. Segregation of jobs, financial institutions, public spaces, retail, housing, and other notions of American prosperity.

For many whites throughout the 1950s, the notion of federal legal and armed mandates of ‘forced integration’ represented a bridge too far in ‘personal’ freedoms and the fallacy of ‘states rights’. The suburbs represented a kinder, more racially coded, and often gated community, free from the problems of the city white residents purposely caused.

The Tax Revolts and the Atlanta Berlin Wall

These problems included purposely defunding the city government via the tax revolts of the 1950s/60s, alongside closing down public recreation centers and removal of white children from public schools due to the announcement of integration, to name a few.

However, in the case of Peyton Road, white Atlantas built an actual blockade to keep African Americans out of their neighborhood of Cascade Heights in 1962. After the subsequent pushback, white Atlantans completely abandoned the Westside of Atlanta for the racially segregated Cobb County.

The 1960s was the tipping point of the white residential exodus from the city limits of Atlanta and the beginnings of the mega-regional growth associated with our never-ending suburbs today.

Metro Atlanta and its suburbs are still growing

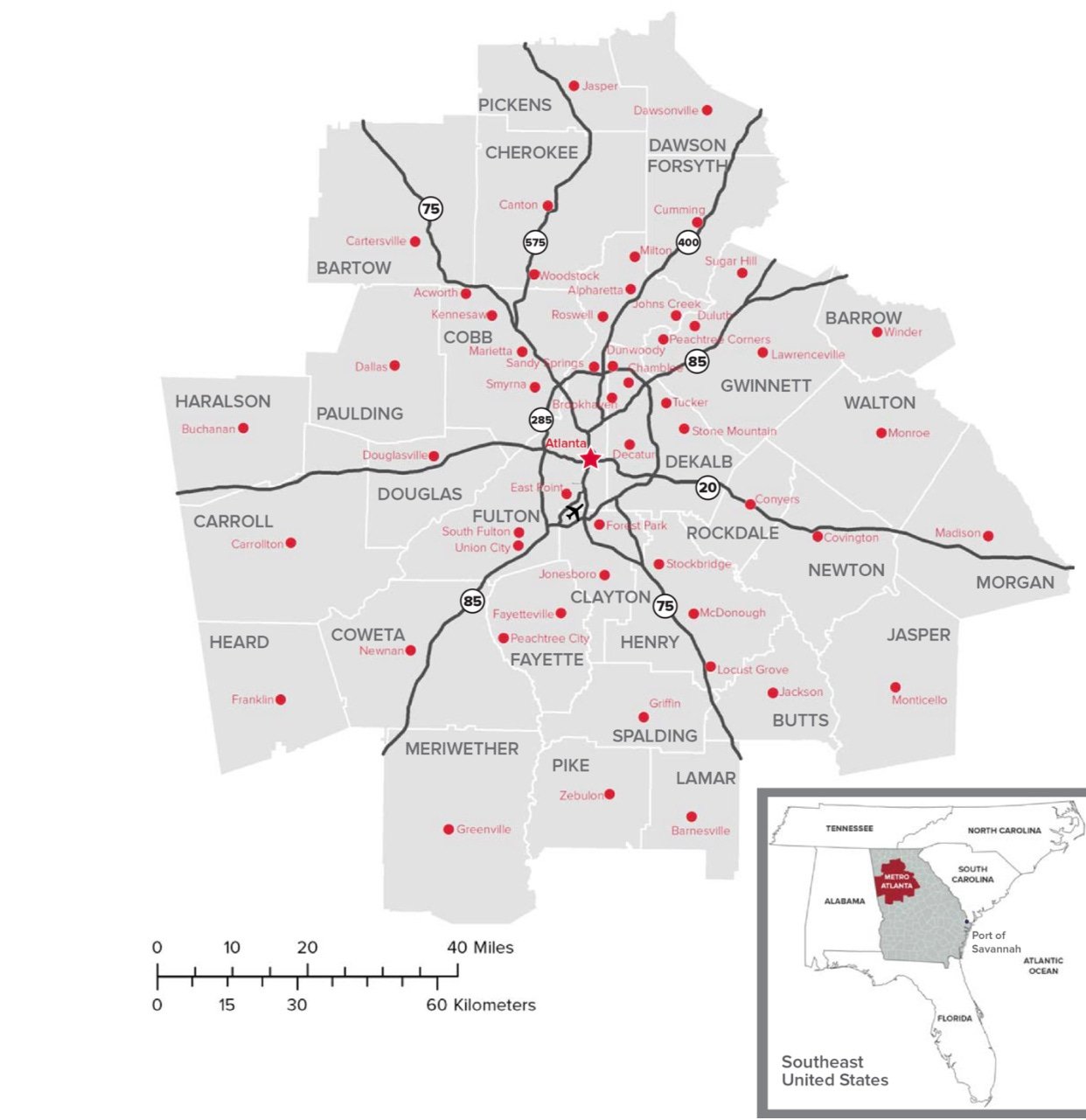

The five core counties of metro Atlanta, Fulton, DeKalb, Gwinnett, Cobb, and Clayton, as they were in 1950, had already expanded to 14 by 1970. Then, it went to 21 in 1990 and 29 by 2010.

As Black wealth expanded in the 1980s and 1990s, many moved into the traditionally White suburbs outside Atlanta. As a result, Whites moved even further out. Whites in North Fulton entrenched themselves just outside Atlanta's city limits.

Initially, it started in the small towns of Roswell, Sandy Springs, and Alpharetta, which turned into suburban cities. On the east side of the metro, White populations moved eastward out of DeKalb County and into Rockdale and Newton Counties. White residential patterns moved even further away from their suburbs during the 1990s, in the 2000s, and throughout the 2010s.

For whites in Cobb, the 1990s saw a further northwest expansion into counties such as Cherokee and Forsyth Counties. Meanwhile, for those in Gwinnett, that suburban expansion moved further north/northeast into towns such as Canton, Woodstock, Dalton, and Gainsville. And Black homeowners kept following.

IV. Black Flight and Black Migration

Black Flight

One of the more interesting dynamics of metro Atlanta’s growth over the last 50 years has been the growth of metro Black middle and upper class. Unlike other cities that experienced white flight, Atlanta city core did have a population decline, but that was not as distributed within the black community in the city of Atlanta.

As Whites left Atlanta, many African Americans moved to other parts of the city. In doing so, some parts of the city became vibrant as upper-income Black enclaves. Places such as Cascade Heights, are still relatively upper-middle class even today. Others, such as the West End, have had ups and downs over the last 50 years.

Black Migration

The 1970s began Black migration from middle- and lower-income Black spaces to more affluent ones. In the 1970s, many blacks moved further into South Fulton and South DeKalb County. The 1980s became a mass migration of black residents from within the city but also a growing number of black residents from other parts of the country. By the 1990s, DeKalb County had gone from majority white to majority Black, something it is still to this day.

At the same time, South Fulton became almost exclusively Black, with several different enclaves of middle and upper-middle-income Black neighborhoods. And for those blacks who had grown up in the city of Atlanta, many had moved out of Black neighborhoods.

Atlanta has always been ‘The Black Mecca,’ but the 1970s saw another population explosion

One of the biggest contributions to the Biden win of ‘suburban’ Atlanta can be attributed to nearly 50 years of Black suburban growth in metro Atlanta. The growth of the Black suburbs is attributed to two primary factors:

One, the growth of the Black middle class by a never-ending supply of Black college grads

These migration patterns were also aided by a steady influx of Black college students who hadn’t left after graduating since the founding of the AUC in the late 1800s. Then, another boom of new Black residents comprised those who began to attend integrated universities in the metro Atlanta area during the 1960s/1970s. Atlanta’s retention of post-collegiate Blacks has grown year-over-year for decades, culminating in one of the largest educated workforces in the country.

Two, the outgrowth of Atlanta has been seen as ‘The Black Mecca’ since the 1970s.

In a post-Civil Rights era and the twilight of the Black Power movement, the 1970s saw a new wave of Black migration. This Black migration saw opportunities in Atlanta aided by the election of the city’s first Black mayor, Maynard Jackson. Jackson’s insistence on having integrated staff on the city government level and mandating 35% of all contracts at the Atlanta airport provided a boon for a new Black middle class.

Additionally, Jackson was the only Atlanta mayor to put money behind arts and culture programming. This was in addition to the burgeoning Black nightlife scene happening in Southwest Atlanta, a precursor to the club culture of the 1990s-2000s. And as this prosperity for African Americans grew, so did the expansion of Black residents further into South Fulton and deeper into South DeKalb County.

These expansions brought greater political power to Atlanta, DeKalb County, and Fulton County. Not to mention the slow but continual growth of West Indian and African residents in the metro Atlanta area. Many often settle in these same suburbs with already established African-American residents in Fulton, DeKalb, and Gwinnett counties.

V. A growing new POC population filled the suburban Atlanta gaps left by African Americans and Whites

Latinx in metro Atlanta

The 1990s saw an explosion of whites leaving the suburbs they helped found. In northern DeKalb, white residential populations moved further into Gwinnett County and out of that county, leaving a pocket for newly arriving Latinx immigrants to thrive.

These Latinx residents arrived to fill the construction needs of both the 1996 Olympics and a boom in retail/service-based work that accompanied these growing northern suburban expansions. As a result, new housing gaps, filled by the newly arriving Latino residents, opened up.

The backlash against Latinx residents is the biggest reason for a surge in political activity

But despite these populations growing over the years, the Latinx community has been relatively less engaged politically until recent years. This surge in Latinx political interest has risen over the last five years with the campaign and subsequent presidency of the current president, Donald Trump.

But this rhetoric has been more emboldened locally by the 2018 Georgia governor’s race and the role of current Georgia governor, Brian Kemp. It was Kemp who notably, in 2018, ran a state-wide ad campaign that included an assortment of firearms, an explosion of ‘paperwork’, and a pickup truck meant for rounding up ‘illegals’.

Asian Americans in metro Atlanta

The 1990s also saw a population boom in northwest DeKalb County along Buford Highway, especially, but mostly within neighboring Gwinnett County, with tens of thousands of newly arriving Asian Americans over the last three decades. Gwinnett has one of the largest Korean communities in the world, in addition to a large Indian and Pakistani community.

Unlike the African-American, White, and growing Latinx populations, they’ve mostly stayed apolitical. However, when Asian Americans have engaged in politics in the past, it’s mostly been for Republicans until recently.

Georgia has six elected Asian American officials; five are Democrats, and one is a Republican. This includes Sam Park (D), Michelle Au (D), Marvin Lim (D), and Bee Nguyen (D) (the woman who took over Stacey Abrams's seat after she ran for governor in 2018).

Similar to that of the Latinx community, the overt racism echoed by both the Trump administration nationally and locally by Georgia Republican lawmakers has either prompted a wave of first-time voters or shifted voters away from Republican candidates in 2016, 2018, and 2020. Just like their Latinx counterparts, the number of Asian American voters who identify as Republican are much older and are being dwarfed by younger voters who are overwhelmingly Democrat-leaning.

VI. The departure of white populations further from the core of metro Atlanta has kept Atlanta’s suburbs affordable and attractive

One of Atlanta’s (the city and the region) appeals has been its relative affordability and constant availability of various middle-class housing stock.

Today, the metro Atlanta area consists of a core of 10 counties, with a true metro area of 29-ish counties. This continual expansion has made Atlanta a super-region in the US. Places like Birmingham, Alabama, to the west of Atlanta, and Chattanooga, Tennessee, which is northeast of Atlanta, have, in many ways, become a part of the Atlanta metro map.

This is continuing the trend of urbanization and re-concentrating job centers from suburbs and isolating small towns back into city centers. Even with the COVID-19 pandemic, cities and regions around the cities are benefiting the most from these changes.

This year-over-year growth has been mostly from other smaller second and third-tier cities throughout the southeast and migration from big blue cities such as Los Angeles, New York, Detroit, and Chicago. People are also moving from places that are not affordable or less desirable for older residents looking to retire. As a result, Atlanta has seen a demographic swing.

Red state economic development strategies brought the Blue Waves

The last two decades of economic policy in Atlanta and the state of Georgia can be summed up in two words: tax breaks.

These financial incentives have brought in a slew of new businesses, developments, and workers from large, traditional blue regions (i.e. the northeast) and liberal-leaning industries (ex: film, television, and music).

Over the last 15-to-20 years, the state of Georgia, alongside the city of Atlanta, has undergone an economic development campaign that can be best surmised as ‘how much money are will willing to give ___ to move/relocate to the metro Atlanta area?’. These tax breaks have inadvertently brought in many of the wrong type of voters—Democrats, and now the dam may have just burst against the great red wall of obstruction.

VII. Let’s end the notion of ‘the suburbs’ being white and conservative

The suburbs of Atlanta in 2020 are much different than those of 1992. But the legacies of the early 90s, conservative suburban politick need not be forgotten.

Newt Gingrich and the rise of the modern Republican Party

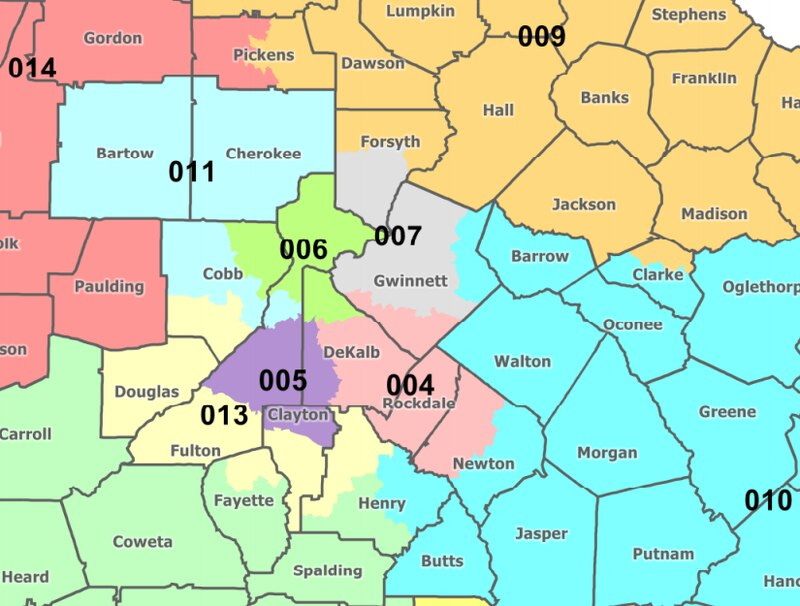

The 1990s saw the rise of the modern Republican party, echoed within the reign of former Georgia congressman Newt Gingrich. Gingrich’s US district-06 comprised the suburbs of north Fulton and Cobb counties. Gingrich represented a new suburban ideology refined on the generation of Baby Boomers who grew up during the end of segregation in Atlanta and raised Gen X/Millennial children/grandchildren.

Gingrich’s style of toxicity in politics saw a GOP pivot towards hyper-partisanship, grandiose gesturings, conspiracies, an embrace of white evangelicalism, dog whistles, and purposely divisive tactics are the proto-version of Trump.

There would be no ‘Make America Great Again,’ the Tea Party, and most of the modern conservative media ecosystem today without Newt Gingrich creating the playbook. But the dirty secret to Newt Gingrich’s (and other statewide GOP politicians') suburban success has been the ability to corral Georgia’s Democratic voters.

This is best seen in the congressional districts of John Lewis’s former District 5. Lewis’s former district (now led by Nikema Williams starting January 2021) places the majority of the city of Atlanta, the mostly Black suburbs, and the towns of south DeKalb County and the mostly Black, north Clayton County into one district. By purposely concentrating these suburbs into two large districts, lawmakers have diluted the Congressional power of non-white voters for nearly three decades.

VIII. Metro Atlanta will now dictate Georgia going forward, freeing the grip of rural, white, and conservative Georgia politics

On top of the layer of gerrymandered congressional districts are the local municipalities and over-represented rural Georgia counties, which have also factored into several down-ballot wins for Dems this year in the state. Many of these wins occur in the growing metro Atlanta area.

With each passing year, these places often become more democratic leaning after each electoral cycle. The presidential totals in 2008 and 2012 would suggest that the Republicans would be in the majority for a while. And depending on who you talk to, the Democratic turnout could be years ahead of schedule.

These surges in the number of new voters, in combination with the increased level of turnout in the 2016 presidential election, as well as 2017’s GA-06 special election or the 2018 Governors race between Stacey Abrams and Brian Kemp, should’ve been the warning signs pointing towards a Biden win. But it’s not just metro Atlanta. Statewide metro areas are the key to winning Georgia going forward. Biden won nearly every major city and county in Georgia, indicating an overall trend toward the Democratic Party.

IX. The future should be blue, but it will likely be purple for a while.

Instead of looking at the 2012 presidential election and 2014 gubernatorial election as confirmation of Republican supremacy in Georgia, we should start to look at them as a sign of peak white conservative turnout. As well as comparing the role of new Latinx and Asian voters for the GOP in 2018 and 2020 as the future of the Republican Party of Georgia.

It would be wise for both political parties to understand that these last two electoral cycles do not reflect a permanent direction for either demographic base and must continue engaging.

The Democrats, if they want to build on this momentum, will have to grow a bigger coalition amongst Latinx and Asian voters in the outer counties. The Dems will also need a new engagement strategy for younger voters 18-29, who, despite showing up more in 2020, still are not at levels at older generations at the polls. The Dems will also need to find a new way to address Black suburban voters, especially Black men, who according to some exit polls, went as high as 18% for President Trump.

I’d love to hear your thoughts!

Very good read!

I remember white flight in the 1960's when East Lake, Kirkwood, Decatur/Dekalb County and Cascade/Ben Hill communities changed drastically from majority white to majority Black neighborhoods. My great-grandparents and an uncle purchased beautiful homes on Mason Avenue in Decatur (near the railroad yard/track, which is another story). My great-grandparents home was still beautiful and well-kept when Edward's Pie Company bought the property in later years.

In many cases of rented homes, white owners would no longer make needed repairs to homes they rented to Blacks, thus causing delapidation and ruin of many rental properties (ghettos); the blame squarely placed on Black renters.

My Dad used his Veteran's Benefits to purchase a home in Ben Hill, which is still a prominent and beautiful Black residential area in Metro Atlanta. White families were jumping out of windows onto moving trucks to "get the heck out of Dodge!" 🤣😂

I hope Georgia remains Blue, but now with an influx of Whites moving back to the city, the State's future is in the air. Democrats must keep working and Metropolitan Atlanta must keep voting out Republicans and others who wish to set Georgia back into the grips of Jim Crow politics.